Introduction

I’ve worked with all kinds of metals in various shops. Over time, I’ve come to see why 316 stainless steel is so widely used. It’s sturdy, corrosion-resistant, and can handle many demanding environments, like marine applications or food-processing lines. Whenever I think about machining 316 stainless steel, I remember the first time I tried to cut it with insufficient coolant. My tool overheated fast, and I had to rethink the entire setup. That experience taught me one simple lesson: 316 stainless steel requires the right approach.

This guide is for anyone who wants to understand the essentials of 316 stainless steel and how to machine it effectively. Whether you’re an engineer, a CNC programmer, or simply an enthusiast curious about different materials, I believe you’ll find something valuable here. I’ll walk through its properties, the machining characteristics, and all the best practices I’ve picked up along the way.

For those involved in custom machining, working with CNC machined parts made from 316 stainless steel presents unique challenges and opportunities. Precision machining plays a crucial role in industries where durability and corrosion resistance are essential, and selecting the right tooling and cutting parameters is key to achieving high-quality results. Understanding how to fine-tune the machining process can help improve efficiency, extend tool life, and ensure consistent part quality.

My goal is to clarify the key aspects of 316 stainless steel. I’ll share some personal encounters with the material and offer tables, data, and real-world examples. You’ll see how to pick the correct tools, optimize cutting speeds, and control costs. I’ll also explore important considerations in quality inspection, show you how to manage supply chain decisions, and discuss future trends.

Because this topic targets both beginners and pros, I’ve tried to keep the language straightforward. I don’t want to drown you in fancy words. But I do want to thoroughly discuss everything from chemical composition to real-life machining workflows, so you can get a holistic view.

Below, I’ll follow a structured path. I’ll start with material properties of 316 stainless steel, then go into machining characteristics, recommended processes, quality control, and cost strategies. I’ll also share some case studies that illustrate solutions to common issues. Finally, you’ll see a conclusion and a detailed FAQ. By the end of this, you’ll have a strong grasp on machining 316 stainless steel and how to optimize it in your own shop.

Material Properties of 316 Stainless Steel

When I first heard about 316 stainless steel, I knew it was a superior grade of stainless steel, but I didn’t fully understand why. Over the years, I learned that its chemical composition, mechanical characteristics, and corrosion resistance all set it apart from simpler forms like 304. Here, I’ll present a thorough breakdown of the material, focusing on what makes 316 stainless steel so suitable for machining, along with reasons why it’s chosen for demanding applications.

2.1 Chemical Composition

316 stainless steel is part of the austenitic stainless steel family. It includes iron, chromium, nickel, and molybdenum as its main alloying elements. The presence of molybdenum is especially important because it significantly enhances corrosion resistance. That’s why 316 stainless steel is a go-to material for marine environments and chemical processing.

- Iron (Fe): Base element for steel, providing general strength and structure.

- Chromium (Cr): Key for forming the passive oxide layer, enhancing oxidation and corrosion resistance.

- Nickel (Ni): Stabilizes the austenitic microstructure, improving ductility and toughness.

- Molybdenum (Mo): Boosts resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion, particularly in chloride-rich environments (like seawater).

- Carbon (C): Typically maintained at low levels to reduce the risk of carbide precipitation that can compromise corrosion resistance.

There are variants within the 316 stainless steel category:

- 316L Stainless Steel: Has lower carbon content, minimizing carbide precipitation during welding. This is extremely useful in high-temperature scenarios where the material might be more prone to sensitization.

- 316Ti Stainless Steel: Contains a small amount of titanium for stabilization, reducing intergranular corrosion, especially at higher temperatures.

I once worked on a heat exchanger project where 316Ti was critical because the operation temperature was continuously hovering around 500–600 °C. Without that titanium, we might’ve risked more rapid corrosion or material failure.

Below is a simplified reference table comparing typical compositions of standard 316 vs. 316L vs. 316Ti. It shows how the minor changes in composition can influence usage:

| Grade | Chromium (Cr) | Nickel (Ni) | Molybdenum (Mo) | Carbon (C) | Titanium (Ti) | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 316 | 16-18.5 | 10-14 | 2-3 | ≤ 0.08 | – | General-purpose corrosion resistance |

| 316L | 16-18.5 | 10-14 | 2-3 | ≤ 0.03 | – | Welded parts, low carbon advantage |

| 316Ti | 16-18.5 | 10-14 | 2-3 | ≤ 0.08 | 0.4-0.7 (typical) | Elevated-temp applications, stabilized |

(Table Note: Actual ranges can vary slightly depending on standards like ASTM A240.)

2.2 Mechanical Properties

Now, let’s talk about the mechanical strength, ductility, and hardness that define 316 stainless steel. In general, 316 stainless steel has a tensile strength around 70,000 psi to 80,000 psi (roughly 485 to 550 MPa). The yield strength is usually in the 30,000 psi (205 MPa) range, and elongation at break can be about 40–50%. I’ve been impressed by how well it can handle strain in certain forming operations.

- Tensile Strength: Often in the 70–80 ksi range.

- Yield Strength: Typically around 30–35 ksi.

- Elongation: Can reach up to 40% or more, indicating high ductility.

- Hardness: Often measured on the Rockwell B scale, typically around HRB 80 or so.

Compared to basic 304 stainless steel, 316 stainless steel provides a similar mechanical profile but better handles chloride exposure, which prevents pitting issues in many real-world applications. That’s why you’ll see 316 stainless steel used in marine hardware, chemical tanks, or even specialized hospital equipment.

2.3 Corrosion Resistance

The big selling point of 316 stainless steel is its corrosion resistance. Because of the chromium and molybdenum content, it forms a passive oxide layer on its surface, which helps shield the underlying metal from corrosive elements. In marine environments, 316 stainless steel has proven to hold up far longer than 304, which is more vulnerable to pitting and crevice corrosion caused by chlorides.

I once visited a coastal facility where we needed to select the right grade for an outdoor pump enclosure. The salty sea air was a constant threat. Going with 316 stainless steel turned out to be the right choice. Three years later, the enclosure still looked almost new, while neighboring carbon steel structures showed significant rust. That’s the reason so many engineers favor 316 stainless steel for coastal or chloride-rich sites.

2.4 Heat Resistance and Other Key Features

316 stainless steel can handle moderate-to-high heat applications, often up to about 1500 °F (815 °C) in intermittent service. But if we’re talking about continuous service, the recommended upper temperature can be a bit lower, typically around 1400 °F (760 °C). If the temperature is consistently high for extended periods, you might consider specialized variants like 316H or 316Ti.

An additional perk is that 316 stainless steel can be welded using most conventional welding processes, like TIG or MIG. If you do plan to weld, remember that 316L’s lower carbon content helps mitigate carbide precipitation, which can degrade corrosion resistance.

2.5 Personal Insight on Selecting 316 Stainless Steel

Whenever I’m in a scenario where I need a material that can handle tough conditions (like chemicals, salt water, or continuous moisture), 316 stainless steel usually tops my list. The trade-off is that it can be more expensive than 304 or mild steel. But if corrosion failure is a major concern, I believe that cost is justified by the durability and lower maintenance over time.

I’ve also seen a variety of attempts to cut corners with cheaper materials, and the result is usually more expensive in the long run. Those experiences inform my strong preference for 316 stainless steel when the environment demands it.

2.6 Where 316 Stainless Steel Shines

- Marine and coastal facilities

- Food and beverage processing equipment (requiring sanitary conditions)

- Chemical processing plants (highly corrosive chemicals)

- Pharmaceutical and biotech equipment (sterile environment, CIP/SIP processes)

- Architectural applications (exposed to weather or harsh environments)

2.7 Conclusion for Chapter 2

Understanding these properties is the bedrock of any successful machining plan for 316 stainless steel. From composition to mechanical behavior, you can see why 316 is especially prized in many industries. Personally, I think its adaptability, corrosion resistance, and decent mechanical strength justify its higher price point.

In the next chapter, I’ll dive into machining characteristics and challenges. If you’re interested in optimizing your cutting speeds and avoiding the pitfalls that come with 316 stainless steel, stay tuned. My hope is that this background sets the stage for a deeper dive into how to machine this material efficiently and effectively.

Machining Characteristics and Challenges (Chapter 3)

When I first started machining 316 stainless steel, I ran into problems like fast tool wear, work hardening, and heat buildup. At the time, I didn’t fully understand the root causes. But after dedicating hours to reading technical materials and performing trial-and-error in the shop, I discovered some common threads. In this chapter, I’d like to walk you through the fundamental machining characteristics of 316 stainless steel, along with the typical hurdles you might face, so you can devise strategies to overcome them.

3.1 The Phenomenon of Work Hardening

316 stainless steel tends to work harden quite readily. Work hardening occurs when the crystal structure of the metal changes due to deformation, resulting in a harder surface layer. The key issue is that if your cutting tool lingers or “rubs” against the material without sufficient penetration, you can inadvertently harden the surface, making subsequent cuts more difficult.

When I first got into CNC machining, I used to slow the feed rate excessively, thinking I was playing it safe. But for 316 stainless steel, that approach backfired. The tool ended up rubbing instead of cutting, creating a hardened skin on the part. That skin quickly wore out my carbide inserts. This is a prime example of how having a “safe” approach can sometimes do more harm than good.

Solution Approach:

- Use a feed rate high enough to ensure the cutting edge pierces through the material.

- Avoid dwelling or excessive tool passes at partial depth.

- Keep your tool sharp and use appropriate tool geometry designed for stainless steel.

3.2 Heat Dissipation and Thermal Conductivity

Compared to many other metals, 316 stainless steel has lower thermal conductivity. This means heat doesn’t diffuse as readily through the material. Instead, it builds up at the cutting zone and in the cutting tool itself. Heat is one of the main factors accelerating tool wear. If you’re not using adequate coolant or your chip evacuation is poor, you can burn through tooling faster than you can order replacements.

I recall an instance where I decided to run 316 stainless steel on an older lathe with suboptimal coolant flow. My inserts were wearing out at an alarming rate, and I kept wondering why. Once I switched to a high-pressure coolant system, I saw an immediate improvement in tool life.

Solution Approach:

- Ensure a steady supply of coolant at the cutting zone.

- Consider a high-pressure coolant system for deeper cuts.

- Keep chips from accumulating; recutting chips generates even more heat.

3.3 Tool Wear and Tool Selection

Stainless steels like 316 are notoriously abrasive, so choosing the right tool material and geometry is critical. If you pick a generic grade meant for mild steel, you’ll likely experience poor tool life. Coated carbide inserts with specialized coatings (like TiAlN or AlCrN) tend to perform well against the friction and heat generated by 316 stainless steel.

Key Considerations:

- Tool Grade: Carbide with a “hard” substrate performs better than conventional HSS in production settings.

- Coating Type: Some coatings provide better heat resistance (e.g., AlTiN, TiAlN) while others excel at handling stainless steel’s abrasiveness.

- Edge Preparation: A slightly honed edge can resist chipping, but too much hone might increase cutting forces.

I often lean toward premium carbide inserts with specialized coatings for stainless steel. It can be pricier initially, but the extended tool life usually offsets that cost. Also, many manufacturers label their tooling specifically for stainless steel or “ISO M” range. Checking those guidelines is a good way to avoid guesswork.

3.4 Cutting Parameters and Best Practices

If you’re dealing with 316 stainless steel, the general rule is to use moderate cutting speeds, a proper feed rate, and maintain enough depth of cut to keep the tool engaged. Here’s a ballpark range for typical operations. Values might differ based on your exact machine, the brand of inserts, and the specific geometry, but this table can serve as a starting point.

| Operation | Cutting Speed (SFM) | Feed (IPR) | Depth of Cut (inch) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turning | 200 – 400 | 0.004 – 0.012 | 0.05 – 0.15 | Use carbide inserts, apply coolant liberally |

| Milling | 250 – 550 | 0.002 – 0.008/tooth | 0.03 – 0.08 | End mills with 4-6 flutes recommended, watch chip evacuation |

| Drilling | 60 – 120 | 0.004 – 0.008 | – | Peck drilling helps control heat; choose short, rigid drills |

| Tapping | – | – | – | Lower RPM, high lubrication, consider thread-forming taps |

(Table Note: SFM = Surface Feet per Minute, IPR = Inches per Revolution. Always verify with tool manufacturer’s guidelines.)

I’ve personally found that milling 316 stainless steel demands more attention to chip evacuation. On more than one occasion, I left chip recutting unchecked and ended up with a crater-worn end mill. By adjusting radial depth of cut and ensuring a consistent chip load, I improved tool life significantly.

3.5 Coolant and Lubrication Strategies

Coolant plays an essential role in controlling the temperature. With 316 stainless steel, I recommend using a high-quality water-soluble or semi-synthetic coolant. Flood cooling is beneficial, but in deep-hole drilling or heavy milling, high-pressure coolant can make a world of difference.

Coolant best practices:

- Keep the coolant concentration within recommended ranges.

- Clean and filter the coolant system regularly to avoid contaminants.

- In drilling operations, especially in deeper holes, consider through-spindle coolant or a peck drilling cycle to reduce heat and chip binding.

3.6 Common Machining Mistakes to Avoid

- Running too slow: Overly conservative speeds or feeds can cause rubbing and work hardening, worsening the situation.

- Using dull tools: Dull edges generate friction, leading to more heat and faster tool wear.

- Ignoring chip evacuation: Stainless steel chips can be stringy, and recutting them escalates tool damage.

- Skipping coolant maintenance: Dirty or inadequate coolant fails to carry heat away effectively.

- Not optimizing tool geometry: Standard inserts for mild steel might not handle stainless effectively.

3.7 My Personal Experience with Tool Trials

I once had a job that involved milling multiple slots in 316 stainless steel for a specialized bracket assembly. Initially, I used a general-purpose end mill. After the first pass, the wear on the cutting edges was so high that the surface finish looked terrible. I recall feeling frustrated and rushed to find a solution.

Eventually, I switched to a carbide end mill specifically engineered for stainless steels. It had a special flute geometry for better chip evacuation and a robust AlTiN coating to handle high temperatures. That alone doubled the tool’s life. When I combined it with a more aggressive coolant approach, my production rate went up by 25%. That’s when I realized how crucial it is to match your tooling to the unique properties of 316 stainless steel.

3.8 Summarizing the Challenges and Solutions

To wrap up the challenges of 316 stainless steel machining:

- Work Hardening: Tackle it with higher feeds, correct tool geometry, and continuous cutting.

- Heat Build-Up: Use proper coolant, maintain good chip evacuation, and pick the right cutting speeds.

- Tool Wear: Invest in specialized inserts or end mills designed for stainless.

- Chip Control: Use strategies like peck drilling, through-spindle coolant, or chip-breaker geometries.

It’s safe to say that 316 stainless steel requires a more deliberate machining approach than lower-alloy steels. If you’re aware of the pitfalls and you adapt accordingly, it becomes quite manageable.

3.9 Transition to Next Chapter

Machining characteristics are one piece of the puzzle. Next, I’ll get into specific machining processes and best practices for turning, milling, drilling, tapping, and even grinding 316 stainless steel. Each process has its own nuances, and I’ve discovered some neat tricks that can save time and money while maintaining quality.

I want to share these insights in detail, so you can replicate or adapt them in your own workshop. By understanding the root causes of the challenges in 316 stainless steel and employing the right combination of speeds, tools, and coolant, you’ll minimize downtime and costly tool replacements.

Stay with me, and we’ll dive deeper into the practical application side of 316 stainless steel machining.

Machining Processes and Best Practices

When I was starting out, I believed that once you understood the basics of cutting parameters, the rest was just pressing “Cycle Start.” But with 316 stainless steel, each machining process brings its own quirks. A single approach seldom works for every operation, so I’ll provide a deeper dive into what I’ve learned for turning, milling, drilling, tapping, and even advanced techniques like high-pressure coolant or cryogenic machining.

4.1 Turning (Lathe Operations)

Turning 316 stainless steel on a lathe requires a disciplined approach. Although turning might seem straightforward, I’ve seen many shops struggle with built-up edge (BUE) and rapid insert wear when cutting corners.

Key Points for Turning:

- Insert Grade and Geometry:

- Use carbide inserts labeled for stainless steel (often “M” grades).

- Look for chipbreakers specifically designed to handle gummy materials like austenitic stainless steels.

- Cutting Speed:

- Ranges from about 200–400 SFM (60–120 m/min).

- I prefer starting in the mid-range (around 300 SFM), then adjusting based on tool wear and finish.

- Feed Rate:

- Stay in the 0.004–0.012 IPR range.

- If feed is too low, you risk work hardening. If it’s too high, you risk tool breakage or poor surface finish.

- Coolant Application:

- Flood coolant is usually sufficient if you have a stable setup.

- For deeper cuts or extended operation, consider high-pressure coolant to flush away chips.

When I turned my first batch of 316 stainless steel shafts, I made the mistake of using the same parameters I used for carbon steel. The result was severe tool nose radius breakdown within minutes. After consulting the insert manufacturer, I switched to a recommended feed rate and replaced my standard insert with a stainless-specific type. My results improved dramatically: longer tool life, consistent surface finish, and minimal work hardening.

4.2 Milling

Milling 316 stainless steel can be tricky due to the potential for heat buildup and chip recutting. End mills, especially, have to cope with the material’s tendency to cling to the cutting edges if there’s insufficient lubrication.

Strategies for Milling Success:

- Tool Choice:

- Use 4- or 5-flute carbide end mills designed for stainless steel.

- I find that variable-helix end mills help reduce chatter and enhance chip evacuation.

- Cutting Speed and Feed per Tooth:

- In the ballpark of 250–550 SFM, though advanced coatings might allow slightly higher speeds.

- Feed per tooth can range from 0.002 to 0.008 inches/tooth, depending on cutter diameter and tool geometry.

- Radial and Axial Depth of Cut:

- Keep radial engagement moderate (often 25–35% of the tool diameter) to avoid too much heat generation.

- Axial depth can be deeper if you have robust fixturing and adequate horsepower.

- Chip Evacuation:

- Use an air blast or coolant to clear chips.

- Recutting chips in 316 stainless steel is a quick way to destroy your end mill’s cutting edge.

- Climb Milling vs. Conventional Milling:

- Climb milling is often recommended with rigid setups to reduce friction and improve surface finish.

- Conventional milling might be safer if your machine or fixture has any instability.

An important personal note: I recall a large project where we had to produce multiple pockets in a 316 stainless steel plate. We initially used conventional milling strategies at a modest speed. Each pocket took longer than we expected, and tool wear was high. When we switched to a “high-efficiency milling” approach with specialized end mills, improved feed rates, and climb milling, we cut the overall machining time by nearly 30%. The difference was night and day.

4.3 Drilling and Tapping

316 stainless steel is also known for being tough to drill, especially for deeper holes. The heat accumulation at the drill tip can lead to rapid wear or even breakage if you don’t apply effective strategies.

4.3.1 Drilling Best Practices:

- Drill Geometry:

- Look for a parabolic flute design if you’re going deeper than 3–4 times diameter.

- Consider cobalt drills or carbide drills with specialized coatings for stainless steel.

- Peck Drilling Cycle:

- This approach helps break chips and remove them from the hole.

- I often set small “peck” increments, especially beyond 2xD hole depths.

- Coolant Delivery:

- Through-spindle coolant is ideal for deep holes.

- At the very least, use a strong external coolant stream or pecking approach.

- Cutting Speed and Feed:

- Typically, 60–120 SFM is recommended for drilling 316 stainless steel.

- Adjust feed carefully, ensuring the drill bites into fresh material on each pass.

4.3.2 Tapping and Threading:

Tapping in 316 stainless steel can be tricky because of the material’s hardness and tendency to gall. I’ve broken a fair share of taps by underestimating torque requirements.

- Tap Selection:

- Use taps specifically labeled for stainless steel.

- Consider forming taps if the application suits it, as they create threads via material deformation rather than cutting.

- Lubrication:

- A dedicated tapping fluid or a thick cutting oil can make a huge difference.

- Flood coolant alone might not be enough; local application of tapping oil helps.

- Tapping Speed:

- Keep the RPM moderate, especially for smaller threads.

- Some folks prefer to hand-tap for small holes to feel the torque buildup.

4.4 Grinding and Finishing

In some applications, you need a refined surface on 316 stainless steel—especially if it’s used in food processing or medical environments. I have friends in the pharmaceutical sector who emphasize the importance of smooth surfaces to prevent bacterial growth.

Grinding Tips:

- Use wheels designed for stainless steel, often made with aluminum oxide or ceramic abrasives.

- Maintain a consistent coolant flow to prevent heat discoloration or warping.

- Keep feed rates slow and uniform to avoid scorching the surface.

For even finer finishes, you might consider mechanical or electropolishing. Electropolishing can enhance corrosion resistance by removing the top layer of material and creating a very clean, passive surface.

4.5 Advanced Techniques

316 stainless steel may benefit from advanced methods like high-pressure coolant (HPC) or cryogenic machining. While these methods can require specialized equipment, they can yield noticeable efficiency gains.

- High-Pressure Coolant (HPC):

- Drives coolant directly into the cutting zone.

- Improves chip breaking in operations like turning and drilling.

- Helps maintain lower tool and workpiece temperatures, extending tool life.

- Cryogenic Machining:

- Uses liquid nitrogen to dramatically reduce cutting temperatures.

- Particularly effective in aerospace or medical parts that demand superior surface integrity.

- CNC Programming Strategies:

- In milling, consider trochoidal or dynamic milling toolpaths.

- These toolpaths maintain consistent cutter engagement and heat distribution.

4.6 Common Pitfalls in Machining Processes

- Improper Tool Setup: Using the wrong insert or tool geometry for stainless steel can lead to immediate failure.

- Excessive Depth of Cut with Insufficient Coolant: This often overheats the tool.

- Overlooking Work-Holding Stability: Vibration can cause chatter marks or break the cutting edge.

- Skipping Test Cuts: It’s wise to do a test pass, especially with new tooling or fixturing.

4.7 My Personal “Light-Bulb Moment”

When I reflect on my experiences, I recall a moment when I was milling a fairly complex 316 stainless steel part with multiple pockets, channels, and holes. I set everything up, pressed the start button, and the tool squealed. Chips were a dull blue, and the machine sounded miserable. Instinct told me I needed to adjust something right away.

I lowered the feed and sped up the RPM. That actually made the squeal worse because I was generating too much heat in the cut. After checking references for stainless steel milling, I realized I had to increase the feed and reduce the surface speed to keep the chip load in an optimal range. The squealing disappeared, the chips turned a bright silver, and my tool life soared. That was a defining moment for me in understanding how machining parameters interplay with the hardness and thermal conductivity of 316 stainless steel.

4.8 Second Data Table – Example Cutting Parameter Ranges (Expanded)

Here’s another table with a bit more detail, breaking down operation type, recommended tool materials, and approximate cutting speeds/feeds. This might help you plan a wide range of 316 stainless steel machining tasks:

| Operation | Tool Type | Cutting Speed (SFM) | Feed Rate Guidelines | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Turning | Carbide Insert (ISO M) | 200 – 400 | 0.004 – 0.012 IPR | Use positive-rake geometry for improved chip flow |

| Internal Boring | Carbide Boring Bar | 150 – 300 | 0.003 – 0.010 IPR | Focus on stable setup, minimize tool stick-out |

| Face Milling | Face Mill w/ Carbide Inserts | 300 – 550 | 0.002 – 0.006 in/tooth | Keep inserts sharpened; watch for built-up edge |

| Pocket Milling | 4 or 5 Flute End Mill | 250 – 500 | 0.002 – 0.010 in/tooth (varies by diameter) | Consider trochoidal milling for complex pockets |

| Drilling (< 1″ dia) | Carbide or Cobalt Drill | 60 – 120 | 0.004 – 0.008 IPR | Peck cycle recommended; flood coolant or through-spindle if available |

| Tapping (Manual) | HSS or Carbide Tap | – | – | Use tapping compound; carefully monitor torque |

| Tapping (Machine) | Form Tap or Cut Tap | – | – | Low RPM, high lubrication; match the tap geometry to thread pitch |

| Grinding | Al Oxide / Ceramic | – | – | Maintain consistent coolant flow; watch surface temperature |

| High-Pressure Coolant Ops | Specialized Carbide Tools | Varied | Varies by operation | HPC can boost chip control, especially in turning and drilling |

(Table Note: Always verify with the specific tool manufacturer for more precise values.)

4.9 Wrapping Up Machining Processes

By understanding the unique demands of 316 stainless steel and selecting the correct tools, speeds, feeds, and coolant strategies, you can achieve excellent results. The key is to remember that 316 stainless steel behaves differently than simpler materials. Adjust your approach accordingly, and you’ll discover that it’s not as daunting as some people claim.

In the next chapter, I’ll discuss how to ensure consistent quality during and after these machining processes, including inspection methods, surface finish requirements, and how to handle potential defects. My personal motto has always been: “What good is an impressive CNC routine if the final product fails inspection?” Quality control ensures that our machined 316 stainless steel parts perform reliably in real-world conditions.

Quality Control and Inspection

When I first began machining 316 stainless steel, I often focused only on the cut itself: the tool, speeds, feeds, and coolant. But as I gained experience, I realized that quality control (QC) and inspection are equally critical. Even if your machining strategy is top-notch, any oversight in monitoring dimensional accuracy, surface finish, or corrosion susceptibility can lead to expensive reworks or failures in service. In this chapter, I’ll share what I’ve learned about setting up robust QC processes for 316 stainless steel parts. This will include dimensional inspection, surface roughness checks, non-destructive testing (NDT), corrosion testing, and best practices for maintaining documentation.

5.1 Dimensional Accuracy and Tolerances

One crucial aspect of quality control is ensuring your 316 stainless steel parts meet the specified tolerances. Stainless steel has a tendency to expand with heat, and 316 is no exception. During extended machining sessions, the part can warm up just enough to alter dimensions slightly. If you’re working on tight tolerances, even a small temperature fluctuation can cause issues.

5.1.1 Strategies to Control Thermal Growth

- Shorter Machining Cycles: Sometimes breaking a long program into smaller segments helps the part cool between operations.

- Coolant Temperature Regulation: If feasible, keep your coolant at a consistent temperature. Large swings in coolant temperature can lead to dimension shifts.

- In-Process Measurements: Use probing routines on CNC machines to detect dimensional deviations. This method helps you correct offsets in real time.

- Stable Fixturing: Vibrations or repeated clamping/unclamping can create dimensional variance. A secure, repeatable fixture is key.

I recall working on a complex 316 stainless steel manifold where we had extremely tight dimensional specs. We utilized an on-machine probe to measure critical bores after each tool pass. That extra step saved us from shipping out-of-tolerance parts.

5.1.2 Gauging Tools and Instruments

Common tools for measuring dimensions in 316 stainless steel parts include:

- Micrometers: Ideal for external diameters or thickness checks.

- Dial/Digital Calipers: Good for quick checks, though not always suitable for ultra-tight tolerances.

- CMM (Coordinate Measuring Machine): Useful for complex geometries, especially when you have multiple holes, angles, or surfaces to inspect.

5.2 Surface Roughness

Surface roughness is another key metric for evaluating the quality of machined 316 stainless steel parts. In industries like food processing, pharmaceuticals, or medical devices, a smooth surface can be crucial for sanitation and performance. A coarse surface might trap contaminants or become a hotspot for bacterial growth.

5.2.1 Common Roughness Parameters

- Ra (Arithmetic Mean Roughness): The average height of surface peaks and valleys. It’s the most commonly cited parameter.

- Rz (Average Maximum Profile Height): The average of the vertical distance from the highest peak to the lowest valley in five sampling lengths.

In practice, I often see Ra < 0.8 µm (around 32 µin) as a common requirement for a wide range of 316 stainless steelparts. Achieving this may require fine-grain abrasives, dedicated finishing tools, or even post-machining treatments like electropolishing.

5.2.2 Improving Surface Finish

- Use Sharp, High-Quality Tools: Worn-out tooling can scratch or tear the material.

- Optimize Feed Rate: Too high a feed can leave visible lines or ridges on the 316 stainless steel surface.

- Minimize Vibrations: Stable fixturing and balanced cutting strategies reduce chatter marks.

- Apply Coolant Properly: Heat and friction degrade finish quality, so keep your tool and work surface cool.

5.3 Non-Destructive Testing (NDT)

Even if parts pass dimension and finish checks, internal or subsurface defects can remain hidden. That’s where NDT techniques come into play. Some applications of 316 stainless steel involve high-pressure systems or critical infrastructures like chemical reactors. In these cases, structural integrity is paramount.

Common NDT Methods for 316 Stainless Steel:

- Dye Penetrant Inspection (DPI): Also called liquid penetrant testing. It reveals surface cracks, seams, or porosity. It’s simple and low-cost but limited to surface flaws.

- Magnetic Particle Testing (MT): Typically used for ferromagnetic materials. Austenitic stainless steels, including 316, are generally non-magnetic, so this method isn’t always suitable.

- Ultrasonic Testing (UT): Great for spotting internal discontinuities or thickness variations. Operators transmit high-frequency sound waves into the material and monitor reflections.

- Radiographic Testing (RT): Uses X-rays or gamma rays to detect internal voids, cracks, or inclusions. It’s effective but can be expensive and requires specialized safety measures.

I once had to manage ultrasonic testing for a large welded 316 stainless steel pipe. The weld zone was critical, and we needed to ensure no internal cracks or lack of fusion. Ultrasonic testing helped confirm everything was solid without cutting open the weld.

5.4 Corrosion Testing

316 stainless steel is known for its corrosion resistance, but certain environments can still pose a challenge. For instance, high-chloride or acidic settings might stress the material. If your application demands proven resistance, you may need to conduct corrosion tests.

5.4.1 Salt Spray Testing

Salt spray tests (ASTM B117) are common in evaluating how parts withstand a corrosive, salty environment. Test durations can range from hours to weeks, depending on how severe the environment is. In my experience, 316 stainless steel parts often last several hundred hours without significant pitting, while lower-grade steels may corrode quickly.

5.4.2 Pitting and Crevice Corrosion Tests

Methods like ASTM G48 measure pitting resistance using ferric chloride solutions. If you’re designing parts for marine applications, these tests can be essential to confirm that your chosen 316 stainless steel variant (316L, 316Ti) meets the necessary thresholds.

5.5 Traceability and Documentation

In regulated industries—such as aerospace, pharmaceutical, and medical device manufacturing—traceability is key. If a defect is found after parts have been shipped, you need to quickly identify all affected batches.

- Material Certifications: Always keep mill test certificates verifying the chemical composition and mechanical properties of your 316 stainless steel.

- Inspection Records: Document every step, from dimensional checks to NDT results. I usually keep a log with date, operator name, and measurement device used.

- Serial Numbers or Batch Codes: Mark parts or packaging so you can trace them back to a specific production run.

5.6 Best Practices for Ongoing Quality Management

Quality control isn’t a single inspection at the end of machining; it’s an ongoing process. Here are a few strategies that have worked for me:

- In-Process Inspection: Rather than waiting until the final part is done, measure critical features mid-cycle. This allows quick adjustments and reduces scrap.

- Statistical Process Control (SPC): Track key measurements across multiple parts. If you notice a trend, like a dimension inching out of tolerance, you can intervene before the problem escalates.

- Employee Training: Machines and measuring tools are only as good as their operators. Teach your team the importance of following protocols, calibrating instruments, and identifying red flags.

- Continuous Improvement: Evaluate each finished batch for areas to refine. Maybe you can reduce tool changes, improve fixturing, or adopt better finishing methods.

5.7 Common Quality Issues and How to Address Them

- Dimensional Drifting: Could be caused by thermal expansion, tool wear, or fixture looseness. Control temperature, use in-process measurements, and maintain tool condition.

- Surface Defects (Scratches, Burrs): Often related to dull tooling or poor chip evacuation. Sharpen or replace tools, ensure adequate coolant.

- Cracks or Porosity (Welded Assemblies): Improve welding parameters, ensure correct filler metals, and perform NDT to catch issues early.

- Corrosion Post-Machining: If you see rust or pitting, verify if passivation or cleaning was done properly. Check for contamination from carbon steel tooling.

- Hazy or Burned Surfaces: High cutting temperatures or friction can cause discoloration. Adjust feed/speed, add coolant, or switch to advanced techniques like high-pressure coolant.

5.8 My Perspective on Quality and 316 Stainless Steel

I’ve come to respect 316 stainless steel for its resilience and reliability, but it demands precise handling to stay that way. Skimping on quality checks might save you time in the short term, but you risk tarnishing your reputation. Once, I saw a batch of 316 stainless steel valves get rejected because of minor dimensional inconsistencies. The cost of scrapping all those machined parts was significant. That memory motivates me to double-check key features, especially when tolerances are tight.

I also learned that choosing a reputable supplier for your raw 316 stainless steel can go a long way. Inferior or mislabeled steel can sabotage your entire process. Proper documentation and verification at every stage—from raw material receipts to final inspection—keeps everything on track.

5.9 Preparing for the Next Steps

Quality control is the glue holding the entire machining process together. In the next chapter, I’ll delve into cost and supply chain considerations. Anyone who’s managed production knows that quality and cost often compete. By understanding the financial elements of 316 stainless steel machining, you can make more informed decisions and strike a balance between quality and profitability.

I hope these insights on QC and inspection prove helpful. My advice: treat inspection as an integral part of the workflow, not an afterthought. With thorough checks in place, you can confidently deliver 316 stainless steel parts that excel in harsh environments and meet strict customer demands. Now let’s move on to optimizing costs and ensuring a stable supply chain for your 316 stainless steel projects.

Cost and Supply Chain Considerations

When we talk about 316 stainless steel machining, quality is only half of the puzzle. The other half is cost and supply chain management. I learned this the hard way when I took on a production run for a series of custom valves. The project’s success hinged not just on perfect tolerances but on delivering parts on time and on budget. In this chapter, I’ll share insights into how the cost of 316 stainless steel machining can be broken down, what key factors drive that cost up or down, and how to manage your supply chain for consistent results.

6.1 Material Sourcing

Securing a reliable source of 316 stainless steel is the foundation of any machining project. Some folks assume that one supplier is as good as another. But in my experience, differences in material quality can make or break your bottom line.

6.1.1 Local vs. Global Suppliers

- Local Suppliers: Shorter lead times and possibly better responsiveness if there’s an emergency. The trade-off is sometimes higher pricing, though not always.

- Global Suppliers: Potentially lower base costs, but longer shipping times and added logistics complexity. Fluctuations in currency rates and customs fees can eat into any cost advantage.

6.1.2 Certifications and Standards

- ASTM and ASME Certifications: Often mandatory in highly regulated sectors, such as pressure vessels or medical devices.

- Mill Test Certificates (MTC): Prove chemical composition and mechanical properties. This is critical to confirm you’re getting real 316 stainless steel.

- ISO, PED, or Other Regional Standards: Depends on your target market or the application’s regulatory environment.

My approach is to maintain at least two qualified suppliers for 316 stainless steel. That way, if one has a sudden backlog or a material shortage, I can pivot. I learned that lesson after a strike at a major steel mill disrupted deliveries for weeks. Having an alternate source saved me from shutting down production.

6.2 Cost Breakdown of Machining 316 Stainless Steel

To optimize costs, you need to understand where money is being spent. People often blame “material cost,” but in reality, the total expense of 316 stainless steel machining comes from multiple factors.

- Raw Material Cost:

- 316 stainless steel is pricier than mild steel or aluminum. You pay for corrosion resistance, durability, and overall performance.

- Watch out for market volatility in nickel and molybdenum prices, as these drive raw cost fluctuations.

- Tooling and Inserts:

- Cutting tools for 316 stainless steel can wear out quickly if you’re not using the right grades or if your process is inefficient.

- High-quality carbide inserts or end mills have a bigger upfront cost but generally pay off in tool life and performance.

- Machine Time:

- 316 stainless steel can’t always be machined at super-high speeds.

- Slower cutting rates, plus careful finishing passes, can mean more machine hours per part.

- Labor and Overhead:

- Skilled operators are essential. If your staff isn’t well-trained on 316 stainless steel specifics, you can face reworks and scrap.

- Overhead includes electricity (especially for high-pressure coolant systems), shop rent, and depreciation on advanced CNC equipment.

- Scrap and Rework:

- Scrap rates can spike if you struggle with work hardening or tool breakage. Each scrapped part represents wasted material and production time.

- Rework adds extra machine time. If a dimension is off, you may salvage the part by re-machining, but that’s an added expense.

- Quality Assurance and Testing:

- NDT (like radiography or ultrasonic testing) can be pricey, but in some industries, it’s non-negotiable.

- Surface roughness checks, dimensional inspections, and process validations also demand time and resources.

6.3 Strategies for Cost Optimization

6.3.1 Invest in the Right Tooling

Cheap tooling might tempt you, but I’ve found that it often raises overall costs. High-grade carbide tools with specialized coatings designed for 316 stainless steel can run at higher speeds and feeds, reducing cycle time and boosting tool life. Though the sticker price is higher, the return on investment typically justifies itself.

6.3.2 Automate Where Possible

- Automated tool changers, pallet changers, or multi-axis setups reduce idle time.

- In-process measurement systems can catch deviations early, preventing scrap.

6.3.3 Optimize Machining Parameters

- Dial in your speeds, feeds, and depths of cut. Trial-and-error is part of the process, but keep logs so you can replicate successful runs.

- Make sure coolant flow is adequate. Overheating or recutting chips can spike your scrap rate.

6.3.4 Batch Production and Scheduling

- If you can group similar parts or operations, you’ll save on setup time.

- I once scheduled small runs of multiple custom parts in random order. After reorganizing into logical groups, I saw a noticeable drop in overhead.

6.3.5 Lean Manufacturing Principles

- Focus on process flow to reduce downtime.

- Use “just in time” inventory to avoid stockpiling expensive 316 stainless steel. But be careful not to run out of stock if lead times spike.

6.4 Inventory and Logistics

316 stainless steel is corrosion-resistant, but you still need to store it properly. Contamination from carbon steel can cause surface rust or compromise the final product’s performance. I keep my stainless bars and plates on racks separated from carbon steel. Some shops even dedicate separate rooms or color-code storage areas to prevent mix-ups.

6.4.1 Lead Times and Forecasting

- If you have consistent demand, lock in supply contracts or request blanket orders to stabilize pricing.

- In uncertain markets, watch for sudden surges in nickel or molybdenum costs. Price hedging might be an option for large operations.

6.4.2 Logistics and Packaging

- 316 stainless steel can be heavy in large quantities. Plan for freight costs, handling equipment, and insurance.

- For export shipments, consider rust-preventive packaging. Even though 316 is corrosion-resistant, you’ll want to guard against mechanical damage or extreme salt spray.

6.5 Example Cost Table for Machining 316 Stainless Steel

Below is a hypothetical table to illustrate how costs might stack up for a batch of 1,000 units of a small part (just as an example). Values are arbitrary and for demonstration only.

| Cost Component | Approx. Percentage of Total | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Material (316 SS) | 30% | Based on per-pound cost of 316 stainless steel |

| Tooling (Inserts, End Mills) | 15% | Higher-grade carbide + specialized coatings |

| Machine Time | 25% | CNC hourly rate depends on overhead and operator wages |

| Labor (Setup, Inspection) | 10% | Skilled operator cost + quality checks |

| Scrap/Waste | 5% | Assumes minor scrap due to operator error or tool breakage |

| QA/NDT | 5% | Could be higher for critical industries (e.g., medical, aerospace) |

| Overhead/Facilities | 10% | Shop utilities, machine depreciation, software, etc. |

(Table Note: Actual percentages will vary significantly depending on your process and the complexity of the parts.)

6.6 Balancing Cost and Quality

The tension between cost and quality is always there. I once tried to reduce tooling expenses by using a generic insert brand for a lower price. But the end result was more tool changes, longer machining time, and higher scrap. Ultimately, the production cost soared. That taught me a crucial lesson: the cheapest route can be the most expensive in the long run.

A well-managed supply chain, combined with a solid process strategy, allows you to deliver top-grade 316 stainless steel components without hemorrhaging money. When you achieve that balance, you’ll earn the trust of your clients and keep your operations profitable.

6.7 My Personal Tips for Cost Control

- Build Relationships with Suppliers: Loyalty often means better payment terms and priority on hot orders.

- Document Everything: From test cuts to final inspection results, keep records. You’ll see trends and be able to refine your processes over time.

- Embrace New Technologies: High-efficiency milling, HPC, or even partial automation might require an upfront investment, but the payback can be impressive.

- Never Overlook Training: An experienced operator who understands the nuances of 316 stainless steel can save thousands in scrap and rework.

6.8 Transition to Next Chapter

Now that we’ve tackled cost and supply chain considerations, the next logical step is to see how all these best practices come together in real scenarios. In Chapter 7, we’ll explore case studies and real-world examples of machining 316 stainless steel, including actual solutions to common production challenges. I believe seeing these principles in action will cement the concepts we’ve discussed so far, giving you confidence to apply them in your own shop.

Case Studies and Real-World Examples

Over the years, I’ve had the privilege (and sometimes the frustration) of tackling a wide range of 316 stainless steelmachining projects. In this chapter, I want to present a few real-world examples that illustrate best practices, pitfalls, and practical tips. Each case study highlights a different facet of working with 316 stainless steel, from intricate valves to large marine components.

7.1 Precision-Machined Valve Components

A few years back, I was contracted to machine valve bodies for a chemical processing plant. The end-user insisted on 316 stainless steel for its corrosion resistance and ability to handle various acidic solutions.

7.1.1 Challenges

- Tight Tolerances: Some bores required ±0.0005″ (±0.0127 mm), which can be challenging with an austenitic stainless like 316.

- Complex Geometry: These bodies had multiple intersecting holes and angled passages. Ensuring correct alignment and no burrs was tricky.

- Surface Finish Requirements: Ra had to be under 16 µin (0.4 µm) on the sealing surfaces for leak-proof performance.

7.1.2 Approach

- High-Performance Tooling: We used carbide reamers and specialized finishing inserts for the final passes.

- In-Process Gauging: After rough machining, we probed each valve body with a CNC touch probe to confirm critical alignment.

- Coolant Strategy: Constant flood coolant, plus a specialized additive to improve lubricity. We also used a dedicated station for deburring with high-pressure air.

7.1.3 Results

- We achieved a consistent finish well within the Ra 16 µin spec.

- Less than 2% scrap rate across 500 units, which was far lower than the client expected.

- The user reported zero leaks after six months in service.

7.2 Custom Marine Hardware

Another memorable project involved producing deck hardware for a yacht manufacturer. This hardware—cleats, hinges, and brackets—had to withstand saltwater exposure. 316 stainless steel was the natural choice.

7.2.1 Key Points

- Corrosion Resistance: The primary reason they picked 316 stainless steel.

- Polished Aesthetics: The yacht manufacturer wanted a near-mirror finish for aesthetic appeal.

- Batch Size: Production runs were around 200 parts at a time, repeated every few months.

7.2.2 Machining and Finishing Steps

- Initial CNC Milling and CNC Turning: We used standard feeds and speeds for 316, ensuring consistent chip evacuation.

- Surface Preparation: We progressed from 320-grit to 600-grit abrasive to remove any tool marks.

- Mechanical Polishing: After the initial abrasive steps, we switched to buffing wheels with polishing compounds.

- Final Passivation: Immersion in a nitric acid solution to restore the oxide layer and ensure corrosion resistance.

7.2.3 Lessons Learned

- Proper polishing can be time-consuming and should be factored into cost estimates.

- If you rush the polishing phase, you might end up with swirl marks or micro-scratches that ruin the look.

- Post-machining passivation is critical when you’re serious about maintaining 316’s corrosion-resistance properties.

7.3 Food-Grade Equipment Parts

At one point, I collaborated with a small food-processing equipment startup. They needed conveyor components, impellers, and brackets made from 316 stainless steel. The biggest concern was sanitation and easy cleaning in daily operation.

7.3.1 Sanitary Standards

- The surfaces had to be free of cracks, crevices, and rough spots where bacteria could accumulate.

- Welding was minimized, but where needed, we used 316L filler rods and carefully polished the seams.

7.3.2 Machining Observations

- Low-Burr Toolpath Strategies: Our CAM software included “sharp corner smoothing” and custom finishing passes to reduce burrs.

- Increased Tool Clearance: We designed fixtures that allowed full edge access, so we could ensure there weren’t hidden burrs after cutting.

7.3.3 Final Outcome

- The startup successfully passed their local food safety inspections.

- Maintenance staff praised how easy it was to clean the equipment.

- That success earned us a stream of repeat orders as the startup grew.

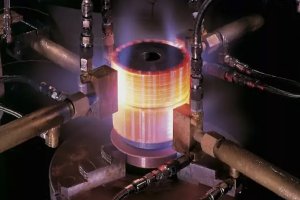

7.4 Heat Exchanger Tubesheets

One of the more complex tasks I’ve undertaken was machining large tubesheets for a heat exchanger. These sheets measured nearly four feet in diameter, with hundreds of precision-drilled holes for tubes. The engineering team chose 316 stainless steel for its strength and corrosion resistance in a high-temperature, chemical-laden environment.

7.4.1 Drilling Over 300 Holes

- We used high-speed steel (HSS) annular cutters for some sections, then switched to carbide drills for deep holes.

- Peck drilling cycles were essential to clear chips and prevent heat buildup.

- Coolant lines had to be carefully positioned to flush out debris.

7.4.2 Tolerance and Warp Management

- Large parts can warp under stress or heat. We scheduled multiple roughing passes, letting the part cool in between.

- We performed an intermediate stress-relief step (low-temperature bake) after the initial drilling to minimize distortion.

7.4.3 Outcome

- Achieved the required fit for the tubes with minimal rework.

- The end user reported excellent durability, even under high-pressure fluid flows.

- That project cemented my understanding of how crucial stress management is for big 316 stainless steelcomponents.

7.5 Lessons Learned from Multiple Projects

Across these varied examples, a few themes keep emerging:

- Proper Tooling: Nothing replaces the right tooling grade, geometry, and coating when dealing with 316 stainless steel.

- Coolant and Chip Control: Without enough coolant and effective chip evacuation, you risk tool wear and scrap.

- Quality Assurance: Regular in-process checks reduce rework. For larger or more critical parts, NDT might be mandatory.

- Cost vs. Quality Balance: Cheaper solutions often lead to more problems down the line. Investing in quality up front typically pays off.

- Documentation and Traceability: Whether you’re making marine hardware or food equipment, being able to trace material and processes fosters trust and consistency.

7.6 Personal Reflections

I’ve seen shop owners blame 316 stainless steel for all sorts of production issues—overheating, excessive tool wear, slow cycle times. But time and again, the real culprit was either a mismatch of tooling or parameters, or a lack of good planning. Once you recognize the intricacies of 316 stainless steel and plan around them, the material becomes far less intimidating.

In my opinion, success with 316 stainless steel hinges on a few fundamentals: knowledge, patience, and willingness to adapt. My first attempts were trial by fire. Now, I see each new job as a chance to refine strategies and push the envelope. I’ve come to appreciate how fulfilling it is to deliver robust components that stand the test of harsh environments.

7.7 Moving to the Conclusion

These real-world scenarios underscore the importance of the concepts we’ve discussed in previous chapters. From raw material selection and machining parameters to finishing, inspection, and supply chain management, it all comes together when you work on actual parts for paying customers. In the next (and final) chapter, I’ll provide a concluding overview of 316 stainless steel machining and share thoughts on future trends that might shape how we handle this versatile material.

Conclusion and Future Trends

When I reflect on my journey working with 316 stainless steel, I’m struck by how much I’ve learned—and how much there still is to explore. The material is a staple in industries that demand corrosion resistance, mechanical strength, and reliability under harsh conditions. We’ve covered everything from its chemical composition to advanced machining strategies, cost considerations, and real-world case studies. Now it’s time to bring it all together.

8.1 Summary of Key Points

- Material Properties:

- 316 stainless steel contains molybdenum, which boosts its corrosion resistance compared to 304.

- Variants like 316L or 316Ti address specific needs (weldability, high-temperature performance, etc.).

- Machining Characteristics:

- Tends to work harden if you use low feeds or dwell on the surface.

- Poor thermal conductivity can lead to heat buildup, so coolant strategies are critical.

- Specialized tooling (often carbide with advanced coatings) is vital for efficiency.

- Processes and Best Practices:

- Turning, milling, drilling, and tapping each present unique challenges with 316 stainless steel.

- Thorough chip evacuation and high-quality coolants can dramatically extend tool life.

- Surface finish requirements may demand slower feed rates or special finishing methods.

- Quality Control:

- Dimensional accuracy can shift due to thermal expansion or residual stress.

- Surface roughness and NDT checks are essential in industries like food processing or pressure vessels.

- Documentation and traceability protect both you and your customer from material mix-ups or undiscovered flaws.

- Cost and Supply Chain:

- 316 stainless steel comes with higher raw material costs than simpler alloys.

- The total expense also involves tooling, machine time, labor, scrap, QA, and overhead.

- Maintaining strong supplier relationships and strategic inventory can mitigate risks.

- Case Studies:

- Real-world projects with valves, marine hardware, food equipment, and large tubesheets demonstrate the adaptability of 316 stainless steel.

- A consistent lesson is that focusing on robust processes and quality pays off in lower scrap and happier clients.

8.2 Emerging Technologies

I believe we’re on the cusp of several advancements that will further improve how we machine 316 stainless steel. The same might be true for other materials, but the unique challenges of 316 make certain innovations particularly appealing.

- High-Pressure Coolant (HPC) Systems:

- As HPC becomes more widespread, shops can effectively cool the cutting zone, flush chips, and prevent heat accumulation in 316 stainless steel.

- I foresee HPC eventually becoming a standard for many stainless steel operations.

- Cryogenic Machining:

- Injecting liquid nitrogen at the cutting edge can yield significant tool-life benefits.

- While still niche, cryogenic machining is worth watching, especially for aerospace-grade components or high-volume production runs.

- Additive Manufacturing (AM):

- 316L is a popular choice in metal 3D printing. Complex geometries are possible, though post-process CNC finishing often remains necessary for critical surfaces.

- Hybrid machines that combine AM and subtractive processes might become more common, especially for prototypes or custom parts.

- Advanced Tool Coatings and Materials:

- Manufacturers keep refining carbide substrates and coatings. We might see coatings specifically tailored to handle the thermal and mechanical stresses of 316 stainless steel.

- Cermet or ceramic tools could see broader application as technology improves.

- Digital Twins and AI-Powered Process Optimization:

- Offline simulations can predict cutting forces, heat buildup, and tool deflection.

- AI algorithms might eventually recommend optimal parameters in real time, reducing the need for manual trial-and-error.

8.3 Sustainability and Environmental Impact

Environmental considerations are playing an increasingly central role in manufacturing. 316 stainless steel is already known for its durability and recyclability. When a 316 part reaches the end of its life, the metal can be recycled into new stainless steel with minimal material loss.

- Coolant Management: Shops are moving toward water-soluble or semi-synthetic coolants that pose fewer disposal hazards.

- Energy Efficiency: CNC machines with regenerative drives or LED lighting reduce the carbon footprint.

- Material Utilization: As we refine processes, we waste fewer raw materials, which is good for both the planet and the balance sheet.

8.4 Final Recommendations

If I had to condense everything into a few quick tips, here’s what I’d say to anyone stepping into 316 stainless steelmachining for the first time:

- Invest in Tooling: High-end inserts or end mills specifically made for stainless steel usually pay for themselves.

- Optimize Speeds and Feeds: Don’t assume slower is better. Use the right parameters to avoid work hardening.

- Coolant is Critical: Whether it’s flood, high-pressure, or cryogenic, proper cooling will make or break your productivity.

- Inspect Early and Often: Catch dimensional drift or surface defects early to reduce scrap and rework.

- Keep Learning: The field evolves. Stay updated on new techniques, coatings, and tools that might cut your cycle time or improve part quality.

8.5 Personal Reflections on Future Collaboration

One aspect I’ve enjoyed is collaborating with peers, from seasoned machinists to bright-eyed engineering students. The more we share our insights, the faster we all improve. I believe 316 stainless steel will remain a mainstay in many industries, and I look forward to seeing new technologies make it even easier to handle.

Sometimes, I imagine a future shop where a combination of additive and subtractive techniques produce fully-finished 316 stainless steel parts in a fraction of today’s lead times. Operators would simply monitor AI-driven systems that continuously adapt feed, speed, and coolant pressure. That might sound futuristic, but the progress I’ve witnessed in the last 10 years alone makes me believe it’s only a matter of time.

8.6 Wrapping Up

We’ve covered a lot of ground in these chapters. From the fundamentals of 316 stainless steel composition to the nitty-gritty of machining strategies, quality control, and cost management, I hope you’ve gained clarity on how to tackle this remarkable alloy. It truly is a versatile workhorse in modern manufacturing.

If you’re new to 316 stainless steel, don’t be intimidated. With the right knowledge, tools, and a bit of patience, you’ll soon discover how rewarding it can be to produce parts that excel in corrosive or demanding environments. If you’re a seasoned pro, maybe a few tips here sparked some fresh ideas for your own operations. Either way, the key is to keep learning and adapting as new technologies come along.

I’ll conclude this journey with one more emphasis on the synergy between science and craft. Machining is part art, part engineering, and part problem-solving. 316 stainless steel just happens to test our skills in all three areas. But once you master it, you’ll have a reliable partner that stands up to the harshest conditions, from deep oceans to sterile labs.

FAQ

- Q: What makes 316 stainless steel more corrosion-resistant than 304?

A: 316 stainless steel contains molybdenum, which enhances its ability to resist pitting and crevice corrosion, especially in chloride-rich or acidic environments. - Q: Do I always need specialized tools for machining 316 stainless steel?

A: Yes. High-quality carbide or ceramic tools with proper coatings can handle the heat and hardness of 316 stainless steel much better than generic tooling. - Q: How do I prevent work hardening during machining?

A: Use sufficient feed, maintain continuous cutting, and avoid rubbing the tool against the part. Proper tool geometry and sharp cutting edges also help. - Q: Is coolant really necessary for all 316 stainless steel operations?

A: Absolutely. Coolant or lubricant reduces heat buildup, minimizes tool wear, and improves surface finish. High-pressure coolant is especially beneficial for deep cuts or drilling. - Q: Can I weld 316 stainless steel without losing corrosion resistance?

A: Yes, but you must use the right filler metal (like 316L) and possibly perform post-weld treatments such as passivation or low-temperature stress relief to preserve corrosion resistance. - Q: Which industries typically use 316 stainless steel?

A: Common sectors include marine, chemical processing, food and beverage, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and heat exchangers. - Q: Why is 316L preferred for welding?

A: 316L has lower carbon content, minimizing the risk of carbide precipitation at weld boundaries, which helps maintain corrosion resistance. - Q: What’s the best way to measure surface roughness on 316 stainless steel parts?

A: A contact profilometer is the most common tool. For very high-precision surfaces, optical methods like interferometry might be used. - Q: Are there any major differences between machining 316Ti and 316L?

A: The basics are similar. 316Ti contains titanium for stabilization at higher temperatures, while 316L has lower carbon to reduce carbide precipitation. Both can be cut with similar parameters, but confirm with your tooling provider. - Q: How do I handle tapping in 316 stainless steel?

A: Use taps specifically made for stainless steel. Consider form taps for better thread strength and liberal lubrication. If you’re power tapping, keep RPM low to avoid galling. - Q: Is additive manufacturing feasible with 316 stainless steel?

A: Yes, 316L is commonly used in metal 3D printing. However, you may still need CNC machining for critical dimensions or surface finishes. - Q: What post-machining treatments maintain corrosion resistance?

A: Passivation and electropolishing are both common. They remove contaminants and restore the protective oxide layer on 316 stainless steel. - Q: Can I save money by buying cheaper inserts?

A: You might reduce upfront tooling costs, but you risk higher scrap rates and more frequent tool changes. In my experience, specialized stainless tooling pays off in the long run. - Q: Why does 316 stainless steel sometimes discolor or form scale during machining?

A: Excessive heat buildup can cause oxidation or scale formation. Adjust your cutting speeds, feeds, and coolant flow to keep temperatures in check. - Q: What are the main standards for 316 stainless steel materials?

A: Common standards include ASTM A240, ASME SA240, and GB/T 3280. Always verify the material certs match your application’s needs. - Q: Any tips for storing 316 stainless steel to prevent contamination?

A: Keep it separate from carbon steels or other metals that can introduce iron contamination. Some shops use dedicated racks or protective plastic films to avoid cross-contamination.

Other Articles You Might Enjoy

- How to Machine 316L Stainless Steel with CNC: Tips and Techniques

Introduction to 316L Stainless Steel in CNC Machining When I first encountered 316L stainless steel, I was struck by its versatility and exceptional properties. It's not just another stainless steel…

- 304 Stainless Steel: Properties, Applications, Machining, and Buying Guide

Introduction I still recall the day I had to choose a material for a small test project back when I was just starting out in fabrication. My mentor insisted on…

- Steel Type Secrets: Boost Your CNC Machining Today

Introduction: Why Care About Steel Types? I’ve always been curious about how the stuff we use—like car engines or tools—gets made so tough and precise. That’s where CNC machining and…

- Galvanized Square Steel and CNC Machining: The Ultimate Guide

Introduction If you're involved in construction, metal fabrication, or precision machining like me, you've probably encountered galvanized square steel. Galvanized square steel is popular due to its strength, corrosion resistance, and…

- VG10 Steel and CNC Machining: The Ultimate Guide

Introduction If you're in manufacturing, custom knife making, or precision machining like I am, you've probably heard about VG10 steel quite often. VG10 steel is well-known in the knife-making world for its…

- AR500 Steel Meets CNC: Your Questions Answered

Introduction: Got Questions About AR500 Steel and CNC? We’ve Got Answers Got a question about machining AR500 steel with CNC? You’re in the right place. AR500 steel is tough stuff—hard,…

- 14c28n Steel CNC Machining Guide: Optimize Your Knife-Making Process

Introduction I still remember the first time I encountered 14c28n steel. I was in a small custom knife shop, chatting with a friend who specialized in premium folding knives. He was telling…

- 5160 Steel Machining Guide: Best Tools, Cutting Speeds & Techniques

Introduction: Why 5160 Steel Machining Matters? I’ve worked around metal fabrication shops for a good chunk of my professional career. One thing I’ve noticed is how often people ask about 5160…

- Mastering D2 Steel CNC Machining: Your Complete Guide

Introduction Overview of D2 Steel and Its Relevance in CNC Machining D2 Steel is a high-carbon, high-chromium tool steel that’s tough as nails and widely loved in the manufacturing world. I’ve seen it pop up everywhere—from knife blades to industrial molds—because of its incredible hardness and wear resistance. When paired with CNC machining, D2 Steel becomes a game-changer for creating precision parts that last. CNC, or Computer Numerical Control, lets us shape this rugged material with accuracy that hand tools can’t touch. For those needing tailored solutions, Custom Machining with D2 Steel offers endless possibilities to meet specific project demands. The result? Flawless CNC machined parts that stand up to the toughest conditions.If you’re searching for "D2 Steel" and how it works with CNC,,you’re in the right place.…

- CNC Machining Material Showdown: 304 vs. 316 Stainless Steel

CNC Machining: An Overview And Importance of Material Selection Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining is a manufacturing process that uses pre-programmed computer software to dictate the movement of factory tools…