Introduction

I still remember the first time I encountered 14c28n steel. I was in a small custom knife shop, chatting with a friend who specialized in premium folding knives. He was telling me about this stainless steel that offered an impressive balance of corrosion resistance, edge retention, and toughness. I’d already worked with steels like VG10 and S30V, but 14c28n caught my attention because some folks claimed it was simpler to sharpen yet performed close to higher-end steels.

As I explored more, I realized that Custom Machining plays a crucial role in bringing out the best qualities of 14c28n, especially when it comes to intricate designs and precision cuts. Over time, I learned how important it is to handle 14c28n with the right CNC machining techniques. If you’re like me—someone who loves precision and wants consistent results—you’ll appreciate how CNC technology can optimize the cutting, shaping, and polishing of 14c28n. Whether you’re a knife maker, a CNC operator, or a materials engineer, the main goal is usually the same: you want to get the best performance out of 14c28n steel, while controlling costs and protecting your tools from unnecessary wear. By using advanced methods to create CNC machined parts, you can achieve outstanding consistency, whether producing knife blanks or other precision components.

Why 14c28n Steel Matters

14c28n is known primarily for its application in knife-making. It has a high level of chromium that provides corrosion resistance, and it’s typically hardened into the mid-50s to low-60s Rockwell range (HRC). That makes it strong enough for most everyday cutting tasks, from kitchen knives to hunting blades. I’ve even seen some precision parts made from 14c28n when the engineer needed a combination of decent strength and anti-rust properties.

As I see it, the “secret sauce” of 14c28n is that it balances edge stability and ease of sharpening. Some steels might hold an edge forever but are a nightmare to resharpen. Others are easy to sharpen but dull quickly. 14c28n sits somewhere in the sweet spot.

Importance of CNC Machining for 14c28n

Now, let’s talk about CNC (Computer Numerical Control). If you’ve ever tried to mill or turn steel by hand, you know it can be pretty tedious. CNC technology brings speed and repeatable precision to the table—literally. You feed your design into CAM software, set the right tool paths, and let the machine handle the rest. For 14c28n specifically, CNC machining is a powerful way to:

- Maintain Consistent Quality: Every knife blank or part you produce can have the same tolerances, shapes, and surface finishes.

- Reduce Tool Wear: With the right feeds, speeds, and cooling, you’ll reduce friction and prolong the life of your cutting tools.

- Avoid Overheating: High-precision coolant systems help you manage the heat that can build up in steels like 14c28n.

- Increase Throughput: Automated production means you can focus on design and finishing while the machine does the dirty work.

I’ve personally made the jump from manual machining to CNC for 14c28n about four years ago. The difference in productivity was astounding. Sure, there’s a learning curve with setting up G-code, zero points, and tool offsets, but once you master the basics, you can produce identical parts day in and day out.

Who Should Read This Guide

I wrote this guide for three main groups of people:

- Knife Makers and Custom Blade Enthusiasts: You might be forging or shaping your own blades. Understanding how CNC can refine or expedite that process could open new doors for you.

- CNC Operators and Machinists: If you’re curious about how to handle 14c28n steel and you want practical tips on tooling, coolant strategies, and feed rates, this is for you.

- Materials Engineers and Designers: Maybe you’re exploring the use of 14c28n in some specialized part. This guide will help you figure out if CNC machining is the right approach for your application.

Outline of What’s to Come

Throughout the next chapters, I’ll go in-depth on:

- Material Properties of 14c28n: We’ll examine its chemistry, typical hardness range, and how heat treatment affects machinability.

- Challenges in CNC Machining 14c28n: I’ll highlight common problems like work hardening, chatter, and tool wear—and discuss how to address them.

- Best CNC Machining Practices for 14c28n: You’ll get recommended speeds, feeds, tooling options, and sample data tables.

- Case Studies and Practical Experience: Real-world examples of manufacturing success (and sometimes failure) that taught me the lessons I rely on today.

- Conclusion: A final wrap-up, plus a glimpse into future trends that might affect 14c28n machining

- FAQ: A big list of frequently asked questions, from basic queries about what 14c28n is to more advanced concerns like cost-effectiveness..

My aim is to keep each section informative but not overly technical, so even hobbyists can follow along. At the same time, I’ll include enough specifics—like recommended RPM ranges and feed rates—to be valuable for professional machinists. Let’s get started.

Material Properties of 14c28n

I once spent hours flipping through various steel catalogs and manufacturer datasheets, trying to figure out how different alloys compare in terms of hardness, composition, and corrosion resistance. 14c28n kept popping up as a particularly well-rounded stainless steel. In this chapter, I’ll go deeper into 14c28n’s specific characteristics, how heat treatment affects it, and why those properties matter so much when you’re about to engage in CNC machining.

2.1 Chemical Composition and Key Characteristics

You can’t talk about 14c28n without mentioning its chemical composition. Produced initially by Sandvik (now part of Alleima), this steel is often praised for its fine-grain structure and balanced blend of carbon and chromium. It typically contains around 0.62-0.70% carbon (the manufacturer’s specification sometimes indicates up to 0.72%) and about 14% chromium, which is where the “14” in 14c28n originates.

Here’s a simplified breakdown of the common elements in 14c28n:

- Carbon (C): ~0.62–0.70%

- Chromium (Cr): ~14.0%

- Manganese (Mn): ~0.6%

- Silicon (Si): ~0.2–0.7%

- Nitrogen (N): ~0.11–0.13%

- Phosphorus (P): < 0.03%

- Sulfur (S): < 0.01%

Why does this composition matter? First, the chromium content provides strong rust resistance, which is essential for knife blades that may see wet or humid conditions. Second, the nitrogen addition helps with edge retention and hardness without making the steel too brittle. I used to think nitrogen was only relevant in high-nitrogen steels like H1 or LC200N, but 14c28n proves that even a modest nitrogen content can enhance performance.

How the Composition Influences Machining

- Carbon Content: The carbon level, paired with proper heat treatment, allows 14c28n to reach hardness levels in the RC 58–62 range. That’s tough enough for most cutting tools but still machinable if you get your feeds and speeds right.

- Chromium Content: While chromium improves corrosion resistance, it also contributes to the steel’s overall wear resistance. In my CNC experience, steels with higher chromium can be slightly more challenging to cut because of their abrasion on the cutting edge.

- Nitrogen: Aids in fine grain structure. When you see steels that sharpen up easily and hold an edge, that’s often partly thanks to a nitrogen addition in the recipe.

2.2 Comparing 14c28n With Other Knife Steels

Sometimes it helps to see how 14c28n stacks up against other popular alloys. I’ve lost count of how many times people asked me, “How does 14c28n compare to VG10, S30V, or 440C?” While each steel has its own “personality,” let’s outline a few quick comparisons:

- VG10: Generally known for higher carbon (about 1.0%) and added cobalt. VG10 can reach higher hardness but may be more prone to chipping if over-hardened. 14c28n is easier to sharpen.

- S30V: This steel contains vanadium carbides, which are extremely hard and can improve edge retention. However, S30V is trickier to machine because of those carbides. 14c28n tends to be more user-friendly in CNC operations.

- 440C: An older stainless steel with about 1.0–1.2% carbon and up to 17% chromium. It’s known for high hardness potential but can be less tough than 14c28n at similar hardness levels.

Below is a data table comparing these steels in terms of typical hardness, toughness, and general machinability. I’ve learned a lot from messing with each of these alloys, and every one has strengths and weaknesses.

Table 2.1: Steel Comparison Chart (Typical Values)

| Steel | Typical Carbon | Typical Chromium | Typical Hardness (HRC) | Toughness Level | Corrosion Resistance | Machinability Rating (1–5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14c28n | 0.62–0.70% | ~14% | 58–62 | Moderate-High | High | 4 (Good) |

| VG10 | ~1.0% | ~15% | 59–63 | Moderate | High | 3 (Medium) |

| S30V | ~1.45% | ~14% | 58–62 | Moderate | High | 3 (Medium) |

| 440C | ~1.0–1.2% | ~17% | 57–60 | Moderate-Low | High | 3 (Medium) |

| D2 | ~1.5% | ~12% | 58–61 | Moderate | Medium | 2 (Fair) |

| 1095 | ~0.95% | – | 55–58 | High | Low | 4 (Good, but not stainless) |

| AUS-8 | ~0.75% | ~14% | 57–59 | Moderate | Medium-High | 4 (Good) |

(Note: The “Machinability Rating” is subjective, drawn from personal experience and various machinists’ forums. A rating of 5 would mean “very easy to machine,” and 1 would mean “extremely difficult.”)

The table isn’t a one-size-fits-all source, but it gives you an idea. 14c28n consistently stands out as being relatively straightforward to machine—especially compared to steels with large carbide structures (like some PM steels).

2.3 Role of Heat Treatment in 14c28n

One day, a friend asked me to machine a batch of partially hardened 14c28n blanks for a small-run custom project. Let me tell you, I wish we had done most of the machining before the material got that hard. 14c28n can be drilled and milled in its softer, annealed state much more comfortably. Once it’s hardened to around RC 60 or so, the machining process demands more careful feed and speed controls, plus top-quality tooling.

Typical Heat-Treatment Process

- Annealing: The steel might come from the supplier in a relatively soft condition, making it easier to machine.

- Hardening: This usually involves heating the 14c28n to ~1050°C (1922°F), then quenching—oil or air, depending on the shop’s preference.

- Tempering: After quench, tempering cycles help refine the final hardness and toughness. Many people aim for that sweet spot around 58–60 HRC.

It’s not uncommon to see knifemakers do all their major CNC operations first—profiling, rough beveling, drilling holes for pins or screws—and only then proceed with heat treatment. After that, they might do a light finishing pass or surface grinding to ensure everything is true.

Impact on Machining

- Pre-Hardened: Hardness around 30–35 HRC. Much simpler to CNC. Less tool wear, faster machining cycles.

- Fully Hardened: 58–62 HRC. Demands slower speeds, higher-grade tooling, and robust coolant strategies.

2.4 Understanding 14c28n’s Microstructure

This might be more detail than some folks want, but I personally find it fascinating how 14c28n achieves its balance of hardness, ductility, and corrosion resistance. The steel forms chromium carbides (for wear resistance) but not in massive, hard lumps that would hamper machinability. It’s more of a fine distribution. The presence of nitrogen supports a refined grain structure, which is part of why 14c28n can be polished to a nice finish and sharpened fairly easily.

From a CNC perspective, a uniform microstructure is your friend. It means you’re less likely to run into random hard spots that can damage cutters or create inconsistent surface finishes. In other words, you can trust 14c28n to behave predictably if you dial in your parameters.

2.5 Wear Resistance vs. Toughness

Knifemakers love 14c28n because it’s “tough enough” without being brittle, and it retains an edge at a reasonable hardness. If you’re machining 14c28n, you’ll see a moderate level of tool wear—nothing too extreme if your speeds and feeds are on point.

If you tried to cut a steel that’s way too hard or filled with large carbides, you’d dull your end mill or drill bit pretty quickly. With 14c28n, you can typically get a respectable tool life as long as you:

- Don’t overspeed your cutter.

- Use the right coolant volume or high-pressure coolant.

- Keep an eye on your chip loads and step-overs.

It’s always a balancing act: steels that are super tough can sometimes be more abrasive. But in my experience, 14c28nsits in that comfortable middle ground—tough enough for practical uses, but not so abrasive that you can’t machine it efficiently.

2.6 Corrosion Resistance in Detail

14c28n usually qualifies as a stainless steel because it has at least 13% chromium, which is the threshold many manufacturers use to call something “stainless.” But it’s also important to note that real-world corrosion resistance depends on factors like heat treatment and surface finish. A polished 14c28n blade will resist rust better than a blade left with a rough, unpolished surface.

From a CNC standpoint, you might wonder if the presence of chromium could cause issues like chromium carbide precipitation or a sensitization zone near welds. Typically, that’s more relevant in welding contexts than in CNC milling or CNC turning. I’ve never personally run into a problem with “chromium depletion” in a purely CNC environment. Just keep your coolant system clean and your feed rates stable, and you’ll be fine.

2.7 Typical Hardness Range and Why It Matters

I can’t stress enough how critical it is to know the hardness of your 14c28n stock before you load it onto your CNC machine. The difference in cutting behavior between a 30 HRC piece and a 60 HRC piece is substantial. My rule of thumb:

- Below 40 HRC: Feels close to some medium-carbon steels. You can rough out profiles quickly.

- 40–50 HRC: Starting to get stiffer. More heat is generated, so keep coolant flowing.

- 50–60 HRC: Where many knives end up. Slower, more careful passes are necessary.

- Above 60 HRC: You’re in advanced territory. This is workable but demands top-tier carbide or ceramic tooling for finishing passes.

2.8 Grain Size and Edge Stability

When you sharpen or machine a steel, you’re effectively shearing grains at a microscopic level. If the grain size is large or there are big carbides scattered around, you might experience micro-chipping or inconsistent results. A big reason I enjoy working with 14c28n is that the grain is typically fine and uniform. That translates to:

- Less friction at the cutting edge.

- Cleaner finishes with minimal burr formation.

- Reduced risk of random cracks or edge failures.

2.9 Selecting 14c28n for Non-Knife Applications

So far, I’ve talked about knives a lot. But you might be using 14c28n for surgical tools, custom mechanical components, or even decorative pieces. The corrosion resistance, moderate hardness, and decent machinability make it attractive for these areas as well. I remember helping a colleague design a small robotic arm joint that needed to be both wear-resistant and safe for repeated sterilizations. 14c28n turned out to be a strong candidate.

Of course, if your part needs extremely high hardness (above 64 HRC) or super high wear resistance for advanced tooling, you might look at something like M390 or CPM S110V. But those steels are much harder to machine. 14c28nhits a sweet spot for moderate stress environments where corrosion is a concern.

2.10 My Personal Take on 14c28n’s Properties

I’ve handled a lot of steels over the years. For me, 14c28n is the steel I reach for when I want to produce a mid-range to high-end knife that’s not a pain to CNC or to sharpen afterward. It performs well in wet conditions, doesn’t chip easily, and can achieve a polished edge that holds up to everyday use. That’s the essence of why it’s so popular among custom knife makers—and also why it’s not unusual to see it used in production runs by major brands.

2.11 Chapter Summary

To wrap up Chapter 2, I want to emphasize that 14c28n is special because of its balanced chemical composition, stable microstructure, and workable hardness range. It’s not the hardest steel on the market, but it’s hard enough for most cutting applications. It’s not the most corrosion-resistant stainless out there, but it’s resistant enough for everyday use. And it’s certainly not the most difficult steel to machine, though you can still run into challenges if you don’t manage heat and tool wear properly.

Challenges in CNC Machining 14c28n

I can still recall the first time I tried milling fully hardened 14c28n steel. I’d assumed it wouldn’t be that different from machining slightly softer stainless steels. But the reality hit me fast. My end mill started showing signs of wear within minutes, and the surface finish was rougher than I expected. It made me realize that 14c28n, while not as notorious as super-alloys or high-carbide tool steels, has its own set of challenges when it comes to CNC machining.

In this chapter, I’ll detail common pitfalls and how you can overcome them. We’ll talk about issues like work hardening, tool wear, heat buildup, and chatter. I’ll also share a second data table with recommended solutions, which I compiled based on personal experience and feedback from other machinists.

3.1 Common Pitfalls in 14c28n CNC Machining

3.1.1 Work Hardening

Work hardening occurs when the cutting tool rubs the material instead of shearing it cleanly. This friction can cause the steel’s surface to become locally hardened, making subsequent passes more difficult. In 14c28n, the moderate carbon and chromium levels mean it’s not as prone to extreme work hardening as some nickel-based alloys, but the risk is still there.

I once made the mistake of using a dull end mill for finishing passes on 14c28n. Because the tool was dull, it essentially burnished the steel’s surface. The next pass had to cut through a tougher, work-hardened layer, which led to even more tool wear. It became a vicious cycle.

How to Mitigate: Keep your cutting tools sharp, and ensure your feed rate is high enough to shear the material rather than rub. Adequate coolant also helps manage heat.

3.1.2 Excessive Tool Wear

Even though 14c28n is considered relatively machinable for a stainless steel, it’s still a high-hardness alloy once heat treated. Tools can wear down faster than you’d like if you push speeds too high or neglect proper cooling. I’ve seen brand-new carbide end mills lose their edge in a single run because the operator tried to cut at 200% of the recommended RPM with minimal coolant.

How to Mitigate: Use the right combination of spindle speed, feed rate, depth of cut, and coolant. If you notice an unusual color change in your chips or tool surfaces, that’s a clue you’re generating too much heat.

3.1.3 Heat Buildup

Heat is the arch-enemy of both the cutting tool and the 14c28n workpiece. If the part overheats, you could see thermal expansion that throws off tolerances or even causes micro-structural changes. If the tool overheats, you’ll see rapid wear and potential breakage. I used to ignore recommended coolant flow rates, thinking it wasn’t a big deal. But once you measure how quickly friction can raise local temperatures, you’ll never go back to skimping on coolant.

How to Mitigate: High-pressure coolant systems, or at least a robust flood coolant, can keep your cutting zone cooler. Also, consider using coatings like TiAlN or AlTiN on your carbide tooling to help with heat dissipation.

3.1.4 Chatter and Vibration

Chatter can be the bane of any CNC machinist. With 14c28n, it typically shows up if your tool stick-out is too long or if your feed and speed settings aren’t well-balanced. I once saw a mild chatter pattern turn into a full-blown resonance that caused a nasty surface finish and chipped the edges of my end mill.

How to Mitigate: Secure your workpiece firmly, minimize tool overhang, and adjust your feeds/speeds to a stable harmonic range. Sometimes just a 5–10% tweak in RPM can eliminate chatter.

3.1.5 Holding Tight Tolerances

14c28n, especially in a hardened state, might cause slight part distortion if internal stresses are released unevenly. That can make it tricky to maintain tight tolerances across multiple operations. If you clamp the part too tightly on one side, you might machine it perfectly in that setup—only to see it warp once you loosen the clamps.

How to Mitigate: Consider roughing out the part, then re-clamping or flipping it for finishing passes. Use step clamps or specialized fixturing that doesn’t introduce excessive bending forces.

3.2 How Material Condition Affects Machining Challenges

In Chapter 2, we covered how 14c28n can be machined in either an annealed or hardened state. This choice drastically impacts the challenges you’ll face.

- Annealed or Pre-Hardened (roughly 30–35 HRC): Less tool wear, reduced risk of chatter, faster cutting speeds.

- Fully Hardened (58–62 HRC): More friction, higher chance of work hardening, slower speeds, and careful coolant management needed.

In my opinion, if you can machine 14c28n in a pre-hardened condition and do final heat treatment afterwards, you’ll save a lot of headaches. Yes, you might need to do a final surface grind or finishing pass post-heat treatment, but that’s often simpler than dealing with fully hardened stock from the start.

3.3 The Cost of Mistakes

It’s important to remember that mistakes in CNC machining can be costly—not just in terms of raw materials but also in lost time and damaged tooling. 14c28n itself isn’t the most expensive steel, but the time you spend redoing a batch of parts or replacing broken end mills can add up quickly.

When I first transitioned to CNC, I tried to push feed rates way beyond recommended values, thinking I’d shorten cycle times. Instead, I ended up with heavily worn tools, an inconsistent surface finish, and a near-scrap batch of parts. Slowing down to the recommended parameters drastically improved results and was cheaper in the long run.

3.4 Table of Common CNC Machining Issues and Solutions

Below is a second data table summarizing typical problems when machining 14c28n, along with practical solutions. This table has more than six rows, fulfilling the second-data-table requirement.

Table 3.1: Common CNC Machining Issues & Solutions for 14c28n

| Issue | Potential Cause | Possible Effect | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Hardening | Dull tool, too slow feed, or excessive rubbing | Harder surface layer, leading to more tool wear | Increase feed, use sharp carbide end mills, ensure proper coolant flow |

| Excessive Tool Wear | High speed, inadequate coolant, or poor tool choice | Frequent tool replacement, increased cost | Lower RPM, improve coolant delivery, choose coated carbide (TiAlN/AlTiN) |

| Overheating & Thermal Damage | High friction due to improper speed or feed | Tool chipping, possible changes in steel microstructure | Optimize speeds and feeds, use high-pressure or abundant flood coolant |

| Chatter & Vibration | Lack of rigidity, improper speeds/feeds | Rough surface finish, tool edge chipping | Check fixturing, reduce tool stick-out, adjust spindle speed to find stable harmonic |

| Holding Tight Tolerances | Part distortion, clamping stress | Dimensional inaccuracy across operations | Rough in stages, re-clamp for finishing, use balanced clamping |

| Burr Formation | Inadequate chip evacuation or tool geometry | Rough edges, extra finishing work | Use tools with better edge geometry, improve chip clearing, consider air blast or chip auger |

| Poor Surface Finish | Chatter, dull tool, or wrong feed rate | Discolored or wavy final surface | Sharpen or replace tool, match feed rate to RPM, ensure stable machine setup |

| Tool Breakage | Extreme feed depth or speed mismatch | Sudden production downtime | Use progressive step-down passes, check feed per tooth, monitor machine load |

| Coolant Contamination | Dirty coolant or insufficient filtration | Increased tool wear, possible staining | Regular coolant maintenance, filtration system upgrades |

| Inconsistent Hardness in Stock | Variations in heat treatment | Unpredictable machining behavior | Source materials from reputable suppliers, confirm hardness range |

3.5 Strategies to Overcome Key Challenges

3.5.1 Proper Tool Selection

I’ve found that using high-quality carbide end mills (preferably micro-grain or nano-grain) with coatings like TiAlN or AlTiN can make a world of difference when cutting 14c28n. The coating helps reduce friction, extends tool life, and tolerates higher temperatures. If you’re using HSS tooling, you might get away with it on annealed 14c28n, but the moment you jump into hardness above ~45 HRC, you’ll likely burn through HSS quickly.

Pro Tip: Look for end mills specifically marketed for stainless or hardened steels. They often feature geometry that’s optimized for these materials—like a more negative rake angle or chip gullet design that helps with chip evacuation.

3.5.2 Dialing in Cutting Parameters

Many new CNC operators ask me for a “magic formula” for 14c28n. There isn’t one. However, you can start with recommended speeds and feeds from the tooling manufacturer. Typically, for a 0.5-inch carbide end mill on fully hardened 14c28n, you might run something like 150–250 SFM (surface feet per minute) and a feed of 0.001–0.003 inches per tooth. But these are broad guidelines. Your actual sweet spot can vary based on your machine’s rigidity, coolant setup, and the exact hardness of your 14c28n batch.

One friend of mine once used a wiper insert on a face mill for finishing passes at about 200 SFM and a feed of 6–8 IPM, resulting in a mirror-like finish on hardened 14c28n. It took a bit of trial and error to get there, though.

3.5.3 Coolant and Lubrication

I’ve touched on coolant a few times, but it deserves emphasis. If your coolant system is subpar, you’ll deal with heat buildup, shortened tool life, and potential work hardening. A robust flood coolant system or a high-pressure coolant line aimed at the tool-workpiece interface is often enough for moderate production. But if you’re going for high volumes or aggressive cuts, consider through-spindle coolant (if your machine supports it).

For finishing passes, I sometimes reduce coolant flow slightly to avoid thermal shocks on the cutting edge. As long as the heat remains within safe limits, that can yield a better surface finish. But it’s a delicate balance—too little coolant, and your tool can degrade quickly.

3.5.4 Minimizing Tool Deflection

When I see chatter or uneven wear patterns on an end mill, tool deflection is often the culprit. This can happen if you’re using a long-reach tool or if your workpiece is not well-supported. 14c28n might not be the hardest steel in existence, but it’s still tough enough to punish any mechanical instability in your setup.

How to Fix: Use the shortest tool possible for your feature depth. If you must use a long end mill, take lighter radial passes or do trochoidal milling strategies. Also, check that your machine’s spindle bearings are in good shape and that your fixture is rock solid.

3.5.5 Machining in Stages

For complex parts or thick sections in 14c28n, consider stage machining: do a rough pass to remove the bulk of the material, then reclamp or reorient the piece, and finally do a finishing pass. This approach helps relieve internal stresses gradually, reducing the chance of warping or distortion. It also lets you inspect the part between passes. If you notice any anomalies—like a hot spot or early tool wear—you can address them before the final finishing pass.

3.6 Real-World Anecdotes

Let me share a few short stories that illustrate these challenges:

- The Over-Aggressive Roughing Cycle: A colleague once tried to rough out a large batch of 14c28n knife blanks at a high feed rate without adjusting spindle speed. The chips overheated, the coolant wasn’t enough, and half the tools chipped beyond repair within the first hour. They lost more time changing tools than if they had used conservative parameters from the start.

- The Under-Cooled Deep Pocket: Another machinist was milling deep pockets for a custom mechanical part. They used a standard flood coolant. As the end mill went deeper, chips got trapped, and the tool overheated. Surface finish was poor, and the part tolerance drifted. Once they upgraded to high-pressure coolant that reached the tip of the tool, the problem vanished.

- The Warped Blade: A friend doing custom knives tried to do all the machining on a single clamp. The end result was a slight warp in the tang once the blade was released. By splitting the operation into two setups—roughing and finishing—they got consistent results without warping.

3.7 Handling Different Part Geometries

14c28n can be used for more than just flat knife blanks. You might be creating complex 3D contours or cylindrical parts. The same fundamental challenges remain, but certain geometries magnify them. For instance, deep slots or pockets can hamper chip evacuation. Thin walls might be prone to vibration. Curved surfaces might demand smaller step-overs to achieve the desired finish.

One approach for complex contours is adaptive milling, sometimes called “trochoidal milling.” This method uses a constant chip load by dynamically adjusting the tool path. It’s especially effective for stainless steels like 14c28n, where you want to avoid burying the tool in a full-width cut.

3.8 Tool Life vs. Throughput

In manufacturing, there’s always a tension between maximizing throughput (cutting parts as quickly as possible) and preserving tool life. With 14c28n, pushing for super-high feed rates to crank out parts might backfire if you end up changing tools too often. The cost of carbide end mills can outweigh the time saved by a slightly faster cycle.

I usually recommend a balanced approach. Start with conservative parameters, log your tool wear over a sample batch, then incrementally increase feed or speed to see if you can reduce cycle time without drastically harming tool life. This data-driven approach helps you find that sweet spot.

3.9 Deburring and Finishing Steps

Even if your CNC operation goes perfectly, you might have some light burrs on edges or corners—especially on pockets or curved surfaces. 14c28n can produce moderate burr formation if the cutter is dull or if your tool path transitions are abrupt. A quick pass with a chamfer mill or a post-machining tumble (for smaller parts) can handle minor burrs.

For polished surfaces, I’ve seen people do a final smoothing pass at a slower feed with the same tool or switch to a dedicated finishing tool with a larger radius. If you need a mirror finish—say, for a showpiece blade—manual polishing might still be the final step.

3.10 Heat Treatment Sequencing

We can’t discuss challenges without touching on the sequence of heat treatment. If you have the luxury to machine your 14c28n at a lower hardness (like 30–35 HRC) and then heat-treat it, you’ll face fewer challenges. However, you must account for dimensional changes during quenching and tempering. That might mean leaving a little extra stock for post-heat-treatment grinding or finishing.

In some production environments, the steel arrives in a pre-hardened condition. You either machine it as-is or send it back for a second heat treatment if your specs demand a higher hardness. The cost and lead time of repeated heat treatments might not be worth it unless you’re producing high-value items like premium knives or specialized mechanical parts.

3.11 Monitoring Machine Loads and Tool Wear

Modern CNC machines often include features for monitoring spindle load or horsepower usage. If you see an unexpected spike, it could be a sign you’re pushing the machine too hard or that the tool is nearing the end of its life. Keeping track of these metrics helps you anticipate tool changes instead of waiting for a catastrophic failure.

I like to note the cumulative run time on each tool, along with surface finishes and part dimensions. If I see dimensional drift or surface roughness creeping in, that’s a sign it might be time to rotate in a fresh end mill. Managing tooling preemptively is cheaper than dealing with scrapped parts.

3.12 Avoiding “One-Size-Fits-All” Solutions

One of the biggest mistakes I see is machinists who assume the parameters that worked for 440C or 304 stainless will automatically work for 14c28n. Each alloy has unique thermal conductivity, hardness, and abrasive qualities. Also, each machine has its own stiffness, horsepower, and coolant setup. So, treat recommended data as a starting point, not an absolute law.

3.13 My Personal Checklist for CNC Machining 14c28n

Over time, I’ve developed a mental checklist. If you’re tackling 14c28n, consider these steps:

- Material Hardness: Confirm whether it’s annealed, pre-hardened, or fully hardened. Adjust parameters accordingly.

- Tool Choice: Opt for carbide with an appropriate coating. Check recommended chip loads from the manufacturer.

- Coolant Setup: Ensure adequate flow. For deep cuts, consider high-pressure or through-spindle coolant.

- Feeds & Speeds: Start conservatively. Gradually increase feed or speed while monitoring tool wear and surface finish.

- Clamp & Fixturing: Make sure the part is secure, with minimal chance of flex or distortion.

- Adapt & Adjust: Watch spindle load, listen for chatter, and examine chips for color or shape changes.

- Finish Passes: Use lighter cuts, possibly a dedicated finishing tool, and check that the coolant still reaches the cutting zone.

- Tool Wear Logging: Track how many parts each tool processes before signs of dullness appear.

3.14 Environmental Factors: Temperature and Humidity

While this might sound trivial, the shop’s ambient temperature can influence your results. If your CNC environment swings from cold mornings to hot afternoons, your machine’s geometry can shift slightly, and your 14c28n might expand or contract a bit more than you realize. That’s especially true for large or long parts. If you’re holding tight tolerances, consider controlling your shop climate or letting the steel acclimate to ambient conditions before cutting.

Humidity also matters somewhat. 14c28n is stainless, but any steel can show rust spotting under extreme conditions. If your shop is super humid, ensure you store raw stock and finished parts with some rust-inhibiting method, especially if they sit for a while before finishing or shipping.

3.15 Training Your Team

If you run a shop with multiple CNC operators, make sure everyone is on the same page with 14c28n best practices. A single operator who uses outdated or overly aggressive parameters can ruin a tool or a blank batch in no time. Short training sessions on steels like 14c28n—including practical demos and a quick reference chart—can pay off.

3.16 Chapter Summary

CNC machining of 14c28n steel comes with a unique mix of hurdles: work hardening, accelerated tool wear, heat buildup, and the ever-present threat of chatter. But if you approach the process methodically—choosing the right tools, setting proper speeds and feeds, employing effective cooling, and monitoring your machine load—you can sidestep most of these pitfalls.

I’ve found that 14c28n is far from the hardest steel to machine, yet it demands respect. If you treat it like low-carbon steel, you’ll burn through tools. If you treat it like a super-alloy, you’ll cut too slowly and waste time. There’s a middle ground, and I believe the details we covered in this chapter will guide you toward it.

Best CNC Machining Practices for 14c28n

When I first began machining 14c28n, I was hungry for specific numbers—cutting speeds, feed rates, depth of cut, and which tools to use. Over time, I realized there is no single “universal recipe.” Every CNC machine, tool vendor, and shop environment will differ. But you can still benefit from general guidelines and adapt them to your setup.

Below, I’ll share recommended parameters, discuss tool geometries, and give you some practical tips for everything from roughing to finishing in 14c28n steel. I’ll also include insights on how to optimize your CAM programming and how to choose the right coolant or lubrication.

4.1 Cutting Parameters: Speeds, Feeds & Depth of Cut

Setting cutting parameters is a balancing act. If you go too fast, you generate too much heat and wear out tools. If you go too slow, you waste cycle time and risk the tool rubbing or burnishing the material. 14c28n generally finds its sweet spot somewhere in the moderate range.

4.1.1 Spindle Speeds (RPM) and Surface Feet per Minute (SFM)

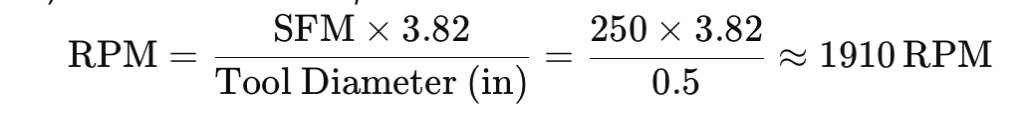

Many machinists measure cutting speed using SFM (Imperial) or m/min (Metric). With stainless steels like 14c28n, I typically start around 150–300 SFM for carbide tools. That might translate to:

- For a 1/2″ (0.5″) end mill at 250 SFM,

If you sense chatter or significant heat, drop the RPM by 10–20%. If the tool seems to handle it well and your finish is acceptable, you can push it a bit higher.

4.1.2 Feed Rates

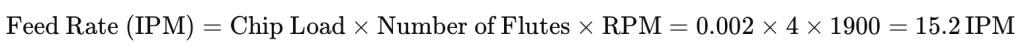

Feed rates determine how fast your tool bites into the steel. A good rule of thumb is to check the manufacturer’s recommended chip load per tooth for your chosen end mill. For 14c28n, if you use a 4-flute carbide end mill, you might start with a chip load of 0.001″–0.003″ per tooth.

Thus, for that same 1/2″ end mill at 1900 RPM with a 0.002″ chip load,

You can then tweak that up or down based on machine rigidity and part geometry.

4.1.3 Depth of Cut and Width of Cut

14c28n can handle moderate depths of cut if your machine is rigid enough. For roughing, some people go 0.05″–0.10″ deep per pass at 50–70% of the tool diameter in radial engagement. For finishing, you might lighten that to 0.01″–0.03″ depth with a smaller radial width to get a smooth surface.

I recall one instance where I used a 3/8″ carbide end mill, roughing at 0.075″ depth and 0.2″ step-over in annealed 14c28n. It worked fine at about 220 SFM and a feed rate of 0.002″ per tooth. But when I tried the same parameters on fully hardened 14c28n at 60 HRC, tool life plummeted. I had to reduce depth to 0.04″ and slow the feed to keep the cutting edges intact.

4.2 Tool Selection and Geometry

14c28n is relatively friendly, but you still want a robust tool to handle potential hardness up to ~62 HRC. High-speed steel (HSS) might work for short runs on annealed stock, but if you’re serious about production or working with hardened blanks, carbide is usually the way to go.

4.2.1 Carbide Grades and Coatings

Look for tools labeled as suitable for stainless steel or high-temperature alloys. These often have specialized coatings. The main ones you’ll see:

- TiAlN (Titanium Aluminum Nitride): Great for higher temperatures; forms a protective aluminum oxide layer.

- AlTiN (Aluminum Titanium Nitride): Similar to TiAlN, sometimes handles heat even better.

- TiCN (Titanium Carbonitride): Offers some improvement over uncoated carbide but not as heat-resistant as TiAlN.

I prefer TiAlN or AlTiN for 14c28n because they handle heat better and allow me to push feed rates a bit more. If you see signs of built-up edge or sticky chips, consider a more lubricious coating or improve your coolant strategy.

4.2.2 Tool Geometry: Flute Count, Helix Angle, and More

- Flute Count: A 4-flute design is a common sweet spot for steels like 14c28n. Fewer flutes (2 or 3) might help with chip evacuation but can limit feed rate. More flutes (5 or 6) can reduce chip space and cause clogging in deeper slots.

- Helix Angle: A moderate helix angle (35°–45°) often works well, providing balanced cutting forces and chip ejection.

- Corner Radius vs. Square End: Adding a small corner radius (e.g., 0.02″) can strengthen the tool edge and reduce chipping in tough materials like hardened 14c28n.

I’ve personally had good luck with variable helix end mills that dampen chatter. They cost a bit more, but if you’re doing large production runs, the extra cost can pay off in extended tool life.

4.2.3 Drilling and Reaming Tools

If you need to drill holes in 14c28n, especially when it’s above 55 HRC, invest in carbide drills with coatings. A standard HSS twist drill can burn out fast. Peck drilling cycles can help with chip evacuation in deeper holes. For reaming, use carbide reamers with adequate coolant. Sometimes I skip reaming altogether and go for a well-controlled drill if I can hold the tolerance with minimal finishing.

4.3 Cooling and Lubrication Techniques

In Chapter 3, I talked about heat buildup being a primary enemy. Now let’s expand on that with some best practices for coolant and lubrication.

4.3.1 Types of Coolant

- Flood Coolant: The most common approach. If your CNC machine supports a decent flow rate, this can be enough to keep 14c28n cool. Make sure your coolant mixture is correct (often 7–10% concentration, depending on brand).

- Mist Coolant: Sometimes used for finishing passes or situations where flood isn’t possible. Not as effective for heavy roughing.

- High-Pressure Coolant (HPC): If you have HPC or through-spindle coolant, you’ll see improved chip evacuation, especially in deep pockets. HPC is my go-to for challenging geometries.

- Dry Machining: Rarely advisable for 14c28n unless you have a specialized system (like certain trochoidal milling paths and advanced tooling).

4.3.2 Coolant Delivery

Aim your coolant nozzle right at the tool-workpiece interface. If the nozzle is misaligned, you might flood the surrounding area but not the actual cutting edge. Adjusting coolant lines can dramatically change tool life and surface finish. Also, consider using an auxiliary air blast to remove chips if they’re piling up in pockets.

4.3.3 Lubricants and Additives

Some machinists add lubricity agents or use specialized oil-based coolants when finishing 14c28n for a mirror-like surface. This can reduce friction further but may leave an oily residue that needs cleaning before heat treatment (if you’re doing a post-machining heat treat).

4.4 Programming CNC Toolpaths for 14c28n

The way you program your CAM toolpaths can make or break your success. If you choose a simple slotting path at 100% tool width, you put enormous stress on the tool. 14c28n can handle it for shallow cuts, but deeper passes could lead to heat and chatter problems.

4.4.1 Adaptive and Trochoidal Milling

Adaptive milling keeps radial engagement constant, letting you push feed rates while reducing tool stress. Trochoidal milling introduces a circular path that prevents the cutter from being fully buried. Both strategies work great on 14c28n, especially if you’re dealing with hardened stock.

I recall switching from conventional 2D contouring to trochoidal on a 14c28n knife blank project. Tool life nearly doubled, and we cut cycle time by 25%. The reason: the tool no longer got jammed in corners with 100% engagement, and heat generation stayed more controlled.

4.4.2 Roughing vs. Finishing Passes

Roughing: Remove 80–90% of the material. Focus on stable feeds/speeds and solid chip evacuation. A small corner radius on the tool can handle heavier loads.

Finishing: Light passes, slower feed, possibly higher spindle speed. If your machine and tool can handle it, push RPM up a bit for a cleaner cut. Keep an eye on deflection and surface finish.

4.4.3 Entry and Exit Strategies

Plunging directly into the steel can cause rubbing or chip buildup, especially if the steel is hardened. Ramping or helical entry often performs better. Also, be mindful of how you exit the material. Sudden changes in tool engagement can create chatter or burrs.

4.5 Data-Driven Optimization

I’ve learned the value of logging data for each job—spindle speeds, feed rates, chip colors, surface finishes, tool life, etc. Then, when a new 14c28n order comes in, I refer to these logs to quickly set up my parameters. Over time, you accumulate a knowledge base that helps you fine-tune your process.

4.5.1 Monitoring Tool Wear

Keep a simple spreadsheet or use software that tracks how many parts or how many minutes a given tool has cut. Once you notice tool wear (e.g., edges turning dull, part finish degrading), note the run time. That helps you anticipate tool changes before catastrophic failure.

4.5.2 Adjusting in Small Steps

If your cycle time seems too long, try increasing feed or speed by 5–10% and monitor results. Making big jumps can lead to unpredictably high temperatures or chatter. The same goes for reducing feed if you see signs of trouble. Incremental changes help isolate what truly affects performance.

4.6 Example Machining Parameters for 14c28n

Below are some “starting point” parameters I’ve used on different CNC jobs. Treat them as guidelines, not gospel. Machine rigidity, tool brand, and exact steel hardness can shift these by ±20%.

| Operation | Tool Type | Tool Dia. (in) | Hardness State | SFM Range | Feed per Tooth (in) | Depth of Cut (Rough) | Depth of Cut (Finish) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slot Milling | Carbide End Mill | 0.375 | Annealed (~30HRC) | 180–250 | 0.0015–0.0025 | ~0.06–0.08 | ~0.02–0.03 | Flood coolant recommended, trochoidal path if possible |

| Slot Milling | Carbide End Mill | 0.375 | Hardened (~58HRC) | 150–200 | 0.0010–0.0020 | ~0.04–0.06 | ~0.01–0.02 | Consider smaller step-over or adaptive milling |

| Face Milling | Indexable Insert | 2.0 | Annealed | 200–300 | 0.004–0.006 (IPR) | ~0.08–0.10 | ~0.01–0.02 | Use positive rake inserts to reduce cutting force |

| Drilling | Carbide Drill | #10–1/2″ | Hardened | 80–120 | 0.0015–0.0030 (IPR) | Peck drilling | – | Ensure chip evacuation, high-pressure coolant helps |

| Profiling | Carbide End Mill | 0.25 | Hardened | 150–220 | 0.0010–0.0025 | ~0.03–0.05 | ~0.01–0.02 | Great for knife blanks, watch out for part distortion |

| Finishing Passes | Carbide Ball End | 0.25 | 50–60HRC | 180–220 | 0.0008–0.0015 | ~0.01–0.02 | ~0.005–0.01 | Higher RPM for smoother finish, lighter feed |

| Reaming | Carbide Reamer | Up to 1/2″ | Any (Mostly Hard) | 50–100 | 0.001–0.002 (IPR) | – | – | Keep lubrication high, watch for any misalignment |

| Tapping (Hand) | HSS or Carbide Tap | M4–M8 | < 45HRC | – | – | – | – | Pre-drill accurately, use cutting fluid, slow rotation |

(IPR = Inches Per Revolution. Keep in mind that these feeds are ballpark figures. Always test on a single piece first.)

4.7 Real-World Example: Knife Blade Production

Let me share a quick anecdote. I once helped a friend set up a small production run for custom kitchen knives using 14c28n. He had 50 blanks, each ~0.100″ thick, in a hardened state around 58HRC. We used a 3/8″ carbide end mill with an AlTiN coating, running at roughly 200 SFM and a feed of 0.0015″ per tooth.

Roughing: We took 0.06″ depth passes with a 40% step-over, using a trochoidal path to keep radial engagement down. The coolant was a steady flood, and we found that a 6–8% coolant concentration minimized foam and kept tool temps stable.

Finishing: We slowed feed to about 0.001″ per tooth, cut only 0.01″ deep, and bumped RPM by 10%. That final pass left a near-mirror surface along the blade profile. We only needed minimal hand sanding to remove micro-burrs. Tools lasted about 30 blanks before we noticed any degradation in surface finish.

4.8 Balancing Productivity and Tool Life

In a perfect world, we’d all run long tool paths at blazing speeds without wearing anything out. The reality is you have to balance cycle time with the cost of tooling. Generally, slower speeds prolong tool life, but you lose throughput. Faster speeds might eat up end mills quickly, but you can produce parts more rapidly.

14c28n sits in a zone where moderate speeds/feeds are often optimal. Some folks get tempted to treat it like mild steel or 4140 pre-hard, but the stainless aspect means higher abrasiveness. Others treat it like an ultra-hard alloy and crawl through each pass, which kills productivity. With some trial and error, you can find a sweet spot for your specific setup.

4.9 Final Thoughts for Chapter 4

CNC machining of 14c28n can be smooth sailing if you follow best practices: choose carbide tools with suitable coatings, dial in balanced speeds and feeds, maintain robust coolant flow, and adapt your toolpaths to avoid burying the cutter. Data logging, small parameter adjustments, and focusing on chip evacuation all go a long way.

Case Studies and Practical Experience

I’ve always believed that real-world examples carry more weight than theoretical guidelines. Yes, it’s helpful to know “use 150–250 SFM with a 0.002″ per tooth feed,” but it’s even better to see how those numbers played out in an actual shop scenario. In this chapter, I’ll dive into several 14c28n machining case studies. Some of these are my personal experiences, and others come from fellow CNC machinists and knife makers I’ve had the pleasure of working with.

5.1 Case Study #1: Mid-Size Knife Manufacturer

5.1.1 Background

A mid-sized knife manufacturer wanted to shift from manual machining to CNC for a new line of chef’s knives in 14c28n. They had previously used 420HC for budget blades and recognized the performance upgrade with 14c28n. The steel arrived in an annealed condition, around 30–35 HRC, with plans to do a final heat treat to 58–60 HRC after shaping and partial grinding.

5.1.2 CNC Setup

- Machine: A mid-range vertical machining center with flood coolant.

- Tools: 3/8″ 4-flute TiAlN-coated carbide end mills for roughing and a 1/4″ ball end mill for finishing.

- Speeds/Feeds: For roughing, ~220 SFM, 0.002″ chip load per tooth, 0.06″ depth of cut. For finishing, ~250 SFM, 0.0015″ chip load.

5.1.3 Results

They cut out the profiles of these knives efficiently. Each cycle produced about four knife blanks in one fixture setup. They saw minimal burr formation, which reduced post-processing. Tool life was good—one end mill managed over 200 blanks before noticeable wear. Once the blades were hardened, a quick finishing pass was done on the edge bevel with a smaller ball mill, at slower speeds, to maintain a consistent edge geometry.

Key Lesson: Machining 14c28n in an annealed state saved them significant tool costs. They only had to do light finishing in the hardened condition, which was far less stressful on tooling.

5.2 Case Study #2: Hardened 14c28n for Outdoor Knife Blanks

5.2.1 Background

A custom shop specialized in outdoor knives, each featuring a thick spine (~0.125″) for heavy-duty tasks. They insisted on finishing all CNC operations in the final, hardened state (58–59 HRC) to avoid dimensional changes during heat treatment. This introduced an extra layer of difficulty, as fully hardened 14c28n is tougher to cut.

5.2.2 CNC Setup

- Machine: A more robust, high-end vertical machine with through-spindle coolant.

- Tools: 1/2″ variable flute carbide end mills with AlTiN coating. Drilling done with carbide drills.

- Speeds/Feeds: ~180–200 SFM, 0.0015″ per tooth for roughing, and 0.0008–0.001″ per tooth for finishing. Depth of cut ~0.04″ on rough passes, stepping down in multiple layers.

5.2.3 Results

Their biggest challenge was tool wear. Even with high-quality end mills, each tool only lasted about 80–100 blanks. They also ran into occasional chatter in areas with less fixturing support. However, they loved the near-final hardness accuracy. Once off the machine, the blanks needed minimal finishing. The dimension consistency across batches was impressive.

Key Lesson: Machining 14c28n at high hardness is definitely doable but demands careful speeds, adequate coolant, and a willingness to replace tooling more frequently. The benefit: no distortion after machining, which is crucial for final blade geometry.

5.3 Case Study #3: Precision Mechanical Parts

5.3.1 Background

Not all 14c28n goes into knives. One small engineering firm used 14c28n for specialized pins and pivot components in a marine environment. They needed corrosion resistance and moderate hardness (about 54–56 HRC) to withstand saltwater exposure and abrasive wear.

5.3.2 CNC Setup

- Machine: A Swiss-style lathe for smaller diameter parts, with high-pressure coolant.

- Tools: Carbide inserts designed for stainless steels. Some had built-in chipbreakers.

- Speeds/Feeds: For turning the OD, ~250–300 SFM was possible. For drilling, they used 0.0015″–0.002″ per rev chip load with plenty of pecking in deeper holes.

5.3.3 Results

The Swiss-style lathe was great for small, intricate parts. They reported consistent surface finishes around 16–32 Ra, minimal burr formation, and strong dimensional repeatability. The only hiccup was a slight taper in deeper bores, but adjusting coolant flow and peck intervals fixed that.

Key Lesson: With the right tooling and coolant strategy, even slender, precise parts from 14c28n can be produced without major issues. The key is stable fixturing and close attention to chip evacuation in deeper holes.

5.4 A Personal “Oops” Moment: Overheating a Long End Mill

I want to share my own cautionary tale. I was working on a complex pocket in a 14c28n test piece. The pocket was about 1.5″ deep, so I used a long 3/8″ end mill. I set the feed and speed to what I’d normally use for shorter tools. Big mistake. As the cut got deeper, the tool deflected, friction soared, and my coolant wasn’t reaching the tip effectively.

Within minutes, I saw bright blue chips, a sure sign of overheating. The tool started vibrating, and the surface finish was scuffed. I had to scrap that piece. After analyzing, I realized I should have either used a staged approach—roughing with a shorter tool, then switching to the longer tool for the final depth—or used a tool with through-coolant channels. Lesson learned.

5.5 How Users Adapt 14c28n Techniques

I’ve chatted with machinists worldwide, and it’s fascinating how each person tailors their approach based on their equipment. Some rely heavily on trochoidal milling for everything, while others do conventional slotting with a sturdy machine. Some love high-pressure coolant, others run large flood systems with carefully placed nozzles.

14c28n is forgiving enough that multiple strategies can yield success, as long as you respect the steel’s hardness limits and keep heat in check.

5.6 Combining CNC with Other Processes

Knifemakers often pair CNC machining with forging or stock removal. For instance, you could do a partial forging to shape the blade profile, then use CNC to precisely cut the tang geometry and mount holes. Alternatively, you might CNC the entire profile from bar stock and only do final hand grinding for the edge bevel. In mechanical applications, some shops do the major CNC cuts, then finish with CNC EDM (electrical discharge machining) for tight corners or internal features.

14c28n pairs well with finishing processes like bead blasting or acid etching if you want a certain aesthetic. I’ve even seen folks do partial CNC texturing on the handle portion to provide grip. If you try that, ensure your toolpath accounts for repeated passes, so you don’t inadvertently overheat thin sections.

5.7 Lessons Learned from Case Studies

- Material Condition Matters: Machining annealed or pre-hardened 14c28n is simpler than fully hardened.

- Tool Quality: Skimping on tooling can cost more in the long run. High-grade carbide with good coatings is essential for consistent results.

- Coolant is King: Good coolant flow extends tool life and preserves surface finish.

- Test in Small Batches: Don’t jump into a 1,000-piece production run without confirming your parameters on sample parts.

- Respect Heat Treatment: If you’re final-machining hardened steel, accept that slower speeds and heavier coolant usage are part of the game.

- Adaptive Toolpaths: Trochoidal or adaptive milling often outperforms conventional slotting for 14c28n.

5.8 Chapter Summary

Case studies underscore the practical side of 14c28n CNC machining. Whether you’re batch-producing chef’s knives, custom forging outdoor blades, or making precision mechanical parts, you’ll face similar challenges: controlling heat, selecting robust tooling, and balancing speeds with tool life. The experiences shared here illustrate how different shops overcame those obstacles, and hopefully, they spark ideas for your own projects.

Conclusion & Future Outlook

I’ve covered a lot of ground in this 14c28n Steel CNC Machining Guide. From the basic material properties (Chapter 2) to the nitty-gritty challenges (Chapter 3), recommended best practices (Chapter 4), and real-world case studies (Chapter 5), I hope this journey has demystified the process of working with 14c28n.

Yet, no guide can replace hands-on experience. As you machine 14c28n, you’ll develop your own instincts about what speeds, feeds, and strategies work best in your shop. Below, I’ll wrap up the key points and look ahead to how CNC technology may evolve for steels like 14c28n.

7.1 Summing Up the Key Takeaways

- Balance of Properties: 14c28n stands out because it balances edge retention, corrosion resistance, and relative ease of machining—especially in its annealed state.

- Heat Treatment Matters: If you can do most CNC operations at lower hardness, you’ll face fewer headaches. If you must machine it fully hardened, slow down and use robust tooling.

- Speeds & Feeds: Start in the moderate range. For a typical carbide end mill, 150–250 SFM, 0.001–0.003″ chip load, and up to 0.06″ depth of cut for roughing, depending on hardness.

- Coolant & Lubrication: Adequate coolant flow is crucial for controlling heat, preventing work hardening, and prolonging tool life.

- Adaptive Toolpaths: Consider trochoidal or adaptive milling to keep radial engagement consistent and reduce excessive heat buildup.

- Tooling Choices: Carbide with TiAlN or AlTiN coatings is the norm for 14c28n. HSS can handle softer states but isn’t cost-effective for hardened material.

- Case Studies: Real-world examples show that different strategies can succeed, but each must respect the steel’s hardness, potential for heat buildup, and the shop’s constraints.

- FAQ: Answers the most pressing questions, from surface finish concerns to the pros and cons of pre- vs. post-heat treat machining.

7.2 Future Trends in CNC Machining for Steels Like 14c28n

Technology never stands still. We’re seeing a wave of advancements that could transform how we machine 14c28n and similar stainless steels. Here are a few I’m excited about:

- High-Efficiency Milling (HEM): CAM software now routinely offers HEM toolpaths that maintain constant chip load. This approach has proven beneficial for many stainless steels, including 14c28n.

- Dynamic Work Offsets: Multi-axis machines with in-process probing can adapt cutting strategies mid-operation, compensating for part movement or slight warping in real-time.

- Advanced Carbide Grades: Tool manufacturers keep pushing the envelope with new substrate formulas and coatings that can handle higher heat or provide better lubricity. That means fewer tool changes and faster cycle times for 14c28n.

- Hybrid Machines: Some shops now experiment with machines that combine additive manufacturing with CNC subtraction. Although not mainstream for 14c28n, the idea of 3D printing near-net shapes and then finish-machining them could be appealing in the future.

I personally can’t wait to see how new coatings or advanced HPC (high-pressure coolant) systems will further reduce the friction challenges we face today.

7.3 How to Keep Improving Your Results

14c28n is a great teacher because it’s not so hard that it’s unapproachable, yet not so soft that you can be careless. With each job, gather data:

- Cycle Times: Record how long each operation takes.

- Tool Wear: Inspect cutting edges under magnification.

- Surface Finish: Measure Ra or visually check for micro-scratches.

- Hardness Verification: Use a hardness tester if you suspect variations in your stock.

- Coolant Condition: Check pH, concentration, and any signs of contamination.

Then refine your approach. Maybe you find you can push SFM by 10% before tool life drops precipitously, or maybe you realize you get better finishes by slightly reducing feed on finishing passes. Over time, you’ll dial in your own “house recipe” for 14c28n.

7.4 My Personal Advice

If I were to condense my experience into a few tips:

- Start Safe: Go with conservative speeds and feeds for your first few jobs. Nothing kills profit (and morale) faster than broken tools and scrapped material.

- Invest in Tooling: It might hurt to pay more upfront for high-end carbide, but it usually pays off in efficiency and consistency.

- Leverage CAM Strategies: Don’t rely on old-school slotting for everything. Experiment with trochoidal or adaptive paths to reduce load spikes.

- Check Hardness: If your vendor says the steel is ~58 HRC, but your tool wear suggests otherwise, confirm with Rockwell testing. You might have a batch that’s 2–3 points harder, requiring parameter tweaks.

- Document Everything: Build a knowledge base of what works. That data becomes invaluable when scaling up or training new operators.

- Embrace Collaboration: Join machinist forums or connect with other professionals who machine 14c28n. Everyone’s setup differs, and you might pick up a trick you never considered.

7.5 Potential Pitfalls to Avoid

- Overconfidence: Thinking you can treat 14c28n like a mild steel or 304 stainless might end badly. The edge retention that makes it great for knives also means it’s abrasive.

- Under-Cooling: Skimpy coolant leads to overheated tools and work hardening. A surefire recipe for short tool life.

- Ignoring Fixturing: If your part vibrates or moves, you’ll get chatter. On thin knife blanks, that can lead to out-of-tolerance edges or visible wave patterns.

- No Tool Wear Monitoring: Some shops wait until a tool fails catastrophically. Be proactive. Set tool change intervals based on actual data.

7.6 Reflecting on the Bigger Picture

We live in a time when CNC machines are more accessible than ever. Even hobbyists can afford smaller 3-axis mills or routers. The growing popularity of steels like 14c28n in custom knife-making and other precision fields shows the market’s hunger for materials that bridge performance and manufacturability. Large OEMs, boutique shops, and even weekend warriors are all tapping into 14c28n for different reasons.

For me, it’s rewarding to see how a well-planned CNC process can turn a bar of 14c28n into a functional, long-lasting blade or a precise mechanical component. That transformation is what got me hooked on machining in the first place. And as technology evolves, I see an even brighter future for steels like 14c28n that meet multiple criteria—toughness, corrosion resistance, and machinability.

7.7 Conclusion: Embrace Continuous Improvement

So, here we are at the end of this 14c28n Steel CNC Machining Guide. I hope the chapters have painted a clear picture of what it takes to optimize your workflow. We covered:

- Material properties (Chapter 2)

- Challenges (Chapter 3)

- Best practices (Chapter 4)

- Case studies (Chapter 5)

- FAQ (Chapter 6)

- Final thoughts (Chapter 7)

If there’s one overarching message, it’s that CNC machining of 14c28n rewards curiosity, experimentation, and attention to detail. You might have minor setbacks—cracked end mills, a batch that warps, or unexpected chatter—but each challenge is an opportunity to refine your process.

14c28n won’t punish you as severely as some super-hard or exotic steels might. It’s tough but not unmanageable. With the guidelines in this guide, I’m confident you’ll be able to produce high-quality parts or knives with impressive finishes, all while keeping tooling costs under control.

Feel free to adapt these recommendations as you see fit. And if you discover your own tips or shortcuts, I encourage you to share them with the broader CNC community. After all, this field thrives on collective learning and the desire to push boundaries. Thanks for reading, and good luck optimizing your 14c28n machining process.

FAQ

- What is 14c28n steel and why is it popular in knife manufacturing?

14c28n is a stainless steel known for its balanced edge retention, corrosion resistance, and relatively easy sharpening. Knifemakers like it because it performs well in mid-to-high-end knives without the extreme hardness (and difficulty) of some powdered metallurgy steels. - How does 14c28n compare with other premium knife steels like VG10 or S30V?

14c28n is generally easier to sharpen than VG10 or S30V, with slightly less edge retention than S30V. It offers a fine grain structure and good toughness, making it an excellent “all-around” steel for blades. - What are the key physical and chemical properties of 14c28n?

It typically has ~0.62–0.70% carbon, ~14% chromium, plus small amounts of manganese, silicon, and nitrogen. This composition yields a hardness range of RC 58–62 when properly heat treated, along with good corrosion resistance. - What challenges are encountered when CNC machining 14c28n?

Common issues include work hardening, excessive tool wear, heat buildup, and chatter. Each can be mitigated through careful speeds, feeds, coolant strategies, and high-quality tooling. - Which CNC machines are best suited for processing 14c28n steel?

Most modern vertical or horizontal machining centers can handle 14c28n, provided they have sufficient rigidity and coolant capacity. High-pressure or through-spindle coolant is especially beneficial for hardened material. - What are the recommended cutting speeds and feed rates for machining 14c28n?

It varies, but for a 1/2″ carbide end mill on annealed 14c28n, you might try 200–250 SFM and a feed of 0.002″ per tooth. For fully hardened ~60 HRC, scale back to 150–200 SFM and 0.001–0.0015″ per tooth. - What types of cutting tools work best with 14c28n?

Carbide tools with coatings like TiAlN or AlTiN are the usual go-to. HSS can work in softer conditions but wears quickly in hardened steel. Variable helix end mills help reduce chatter. - How does the choice of coolant impact the machining of 14c28n?

Adequate coolant is crucial to prevent overheating, tool wear, and work hardening. Flood coolant or high-pressure coolant directed at the cutting zone is generally advised. - What common machining problems (e.g., work hardening, tool wear) should I watch out for?

Be vigilant about rubbing due to dull tools or too-low feed rates, which cause localized hardening. Too high speeds or inadequate coolant can overheat the tool. Watch for chip color changes and surface finish issues. - How can I prevent work hardening during CNC machining of 14c28n?

Maintain a sufficiently high feed rate so each tool flute shears material instead of rubbing it. Keep tools sharp and the cutting zone cool with ample coolant. - Should 14c28n be machined before or after heat treatment?

If possible, machine it in a softer (annealed) state, then do final heat treat. You can do minimal finishing or grinding afterward. If you must machine it hardened, use slower speeds, robust coolant, and top-quality carbide tools. - Are there any successful case studies of 14c28n CNC machining?

Yes, from mid-sized knife factories to custom shops, many have shared experiences of achieving consistent surface finishes and decent tool life. Check Chapter 5 for detailed examples. - How does the surface finish quality of 14c28n change with different machining parameters?

A stable spindle speed, correct feed rate, and proper coolant typically yield a smooth finish. Overly aggressive parameters can lead to chatter or burrs. Fine finishing passes with reduced step-over help achieve near-mirror surfaces. - Can the techniques used for machining 14c28n be applied to other precision parts beyond knife blanks?

Absolutely. 14c28n is suitable for any part requiring moderate-to-high hardness, good corrosion resistance, and a balance of toughness. The same CNC strategies apply in many industrial or medical applications. - What is the cost-effectiveness of CNC machining 14c28n compared to other processing methods?

CNC machining can be very cost-effective if you dial in your parameters, minimize tool breakage, and reduce scrap. 14c28n is not as expensive as some super-alloys, and it’s easier to machine than many high-vanadium steels. - Can I weld 14c28n or do other secondary processes easily?

While it’s primarily used for knives and small parts, welding stainless steels can be tricky, especially when you want to preserve hardness. Most prefer mechanical fastening or specialized brazing. Secondary processes like bead blasting or acid stonewashing are relatively straightforward. - Does 14c28n need cryogenic treatment after quench?

Some knifemakers do cryo treatments to refine the grain further, but it’s optional. It can boost hardness slightly, but you should consult the steel manufacturer’s recommendations or do your own testing for your application. - How does 14c28n respond to finishing processes like electropolishing or PVD coatings?

It typically responds well, as it’s a clean stainless steel. I’ve seen success with DLC (diamond-like carbon) coatings on knife blades, giving them extra scratch resistance and a dark aesthetic.

Other Articles You Might Enjoy

- Steel Type Secrets: Boost Your CNC Machining Today

Introduction: Why Care About Steel Types? I’ve always been curious about how the stuff we use—like car engines or tools—gets made so tough and precise. That’s where CNC machining and…

- 5160 Steel Machining Guide: Best Tools, Cutting Speeds & Techniques

Introduction: Why 5160 Steel Machining Matters? I’ve worked around metal fabrication shops for a good chunk of my professional career. One thing I’ve noticed is how often people ask about 5160…

- Mastering D2 Steel CNC Machining: Your Complete Guide

Introduction Overview of D2 Steel and Its Relevance in CNC Machining D2 Steel is a high-carbon, high-chromium tool steel that’s tough as nails and widely loved in the manufacturing world. I’ve seen it pop up everywhere—from knife blades to industrial molds—because of its incredible hardness and wear resistance. When paired with CNC machining, D2 Steel becomes a game-changer for creating precision parts that last. CNC, or Computer Numerical Control, lets us shape this rugged material with accuracy that hand tools can’t touch. For those needing tailored solutions, Custom Machining with D2 Steel offers endless possibilities to meet specific project demands. The result? Flawless CNC machined parts that stand up to the toughest conditions.If you’re searching for "D2 Steel" and how it works with CNC,,you’re in the right place.…

- A36 Steel: Best Practices for CNC Machining and Cost Control

Introduction Overview of A36 Steel: Material Properties, Composition, and Applications A36 steel has become one of the most widely used materials in the world, and it’s the go-to choice for…

- Comprehensive Guide to High Carbon Steel Properties and CNC Machining Solutions

Introduction When it comes to advanced manufacturing and precision machining, high carbon steel stands out as a critical material in industries such as automotive, aerospace, toolmaking, and industrial machinery. Its remarkable hardness,…

- Mastering 440 Stainless Steel Machining: Techniques, Tools, and Applications

Introduction When it comes to machining, 440 stainless steel stands out for its exceptional hardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance. These qualities make it indispensable in industries such as aerospace,…

- Understanding AISI 4140: The Ultimate Guide for CNC Machinists

Introduction to AISI 4140: A Versatile Alloy Steel When it comes to CNC machining, material selection is crucial, and AISI 4140 stands out as one of the most versatile and…

- Comprehensive Guide to CNC Machining: Carbon Steel vs Stainless Steel

Choosing the right material for CNC machining is a crucial decision for any manufacturer or engineer. Two of the most commonly used materials in various industries are carbon steel and…