Introduction

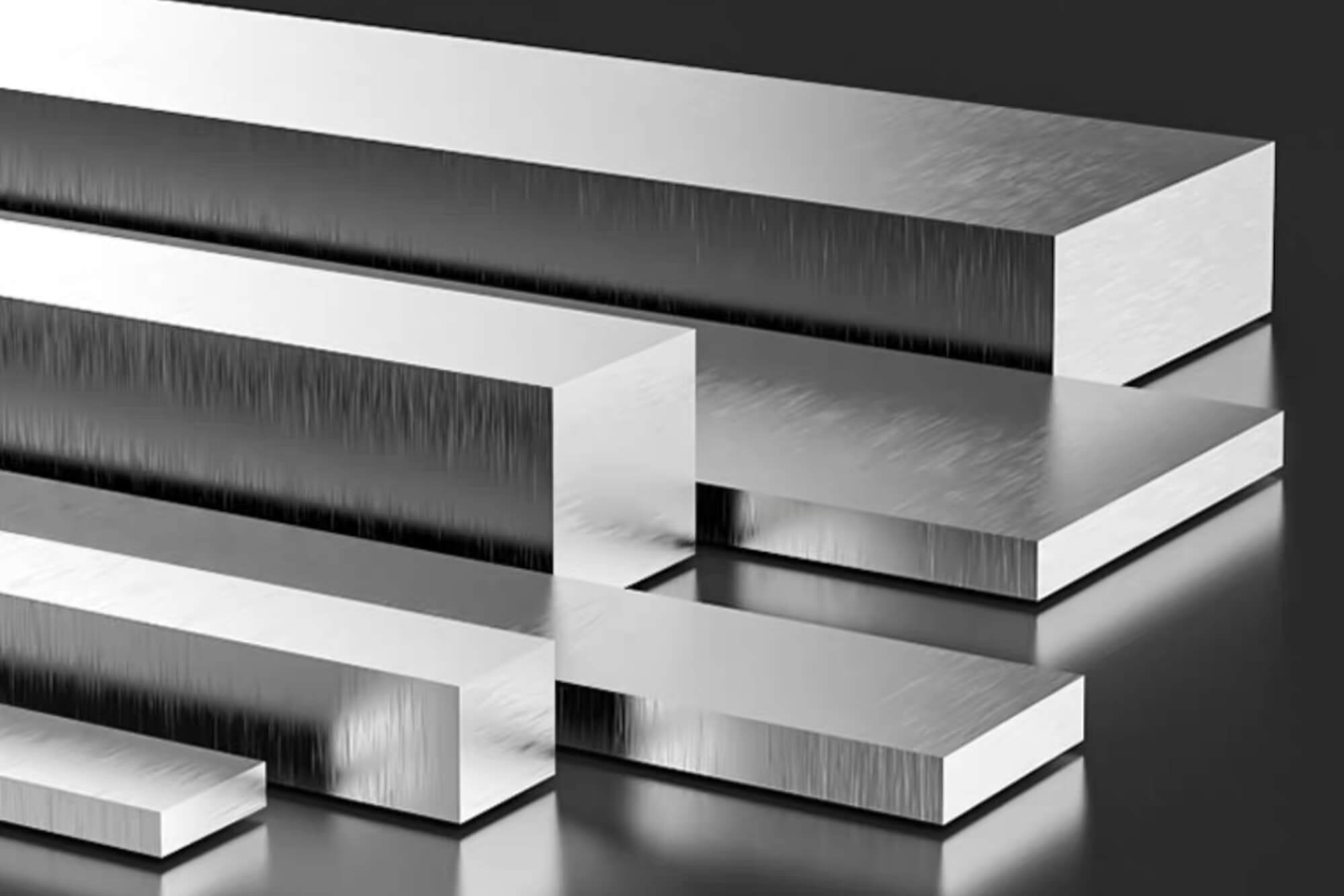

I’ve always found “alloy steel” to be a fascinating subject. There’s so much depth to it, from its versatile chemical composition to the countless industrial applications that rely on its exceptional properties. When we talk about alloy steel, we’re talking about a category of steel that has been enhanced through the addition of various alloying elements. This isn’t just some minor tweak. By adjusting elements like chromium, nickel, molybdenum, and more, we create steels that can handle extreme conditions. In fact, alloy steel belongs to a broader family of iron-based alloys, which also includes stainless steels and superalloys, each designed for specific performance requirements. That’s one reason why alloy steel is frequently used in high-stress environments such as aerospace, automotive, heavy machinery, and more.

But knowing about alloy steel isn’t enough. The real challenge lies in machining it efficiently. Many of us who have worked in machine shops or have run CNC operations can attest that machining alloy steel requires more precision and planning than regular carbon steels. After all, you have to consider aspects like hardness, toughness, and heat resistance. Whether you’re dealing with CNC machined parts for aerospace applications or custom machining intricate components for industrial machinery, achieving high accuracy while maintaining tool longevity is critical. The right approach to machining ensures that finished parts meet the required tolerances while maximizing productivity and cost efficiency.

This is why I decided to craft this comprehensive guide, Alloy Steel Machining Insights: Your One-Stop Guide to Superior Results, to share what I’ve learned through both personal experience and ongoing research.

In this guide, I dive into every major dimension of alloy steel machining. I’ll start with technical analysis and break down the properties of alloy steel that matter most when you’re cutting, drilling, or shaping it. Then, we’ll explore common challenges such as tool wear and heat buildup, along with some of the solutions I’ve discovered (sometimes the hard way) through hands-on trials. You’ll also get insights into emerging technologies in machining, including how digital monitoring tools can help you track tool wear and optimize your cutting parameters in real time.

I’ll follow that with real-world case studies, many of which are drawn from industries like automotive, aerospace, and heavy equipment manufacturing. I’ll also incorporate opinions from experts I’ve met over the years—people who have specialized in alloy steel engineering or next-generation machining solutions. After that, we’ll look at a comprehensive set of guidelines and resources. I want you to come away from this guide not just with theoretical knowledge, but with a practical toolbox you can use to address specific problems you might face in your workshop or production line.

Finally, I’ll wrap everything up with a conclusion and outlook on where I see alloy steel machining headed in the future. Spoiler alert: I believe advanced analytics, machine learning, and continued material innovations will keep pushing the envelope in ways we can’t fully imagine yet.

With that in mind, let’s jump right into the nitty-gritty of alloy steel machining. If you’ve ever struggled with or been curious about this topic, I hope this will be the one-stop guide you’ve been looking for.

Technical Analysis

2.1 Material Properties of Alloy Steel

When I first began working with alloy steel, I was aware that it wasn’t just a single type of steel but rather a broad category. It’s defined by the presence of additional elements like chromium, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, and even tungsten. Each element, in specific proportions, can significantly alter the steel’s behavior under various conditions.

I remember one of my earliest projects where I had to machine a low-alloy steel grade (something akin to 4140). Back then, I didn’t fully grasp why it was more challenging to cut than a simpler carbon steel. I soon learned it was due to the chromium and molybdenum content, which increased toughness and hardenability.

That’s the key with alloy steel: each variant can exhibit very different mechanical and thermal properties. If you’re not careful, you might find yourself snapping tools or generating so much heat that you damage the material’s microstructure. Below is a table that highlights common alloy steel elements and their general effects. I find it helpful to revisit charts like this before starting a new machining project, just to remind myself of the interplay between elements.

| Alloying Element | Typical Range (%) | Primary Effect on Steel | Common Alloy Steel Grades Affected | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromium (Cr) | 0.5–18 | Increases hardness, corrosion resistance | 4140, 4340, 5150 | Key for stainless and heat-resistant steels |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | 0.2–1 | Boosts toughness, creep resistance | 4140, 4340, 8630 | Helps retain strength under high temperatures |

| Nickel (Ni) | 1–5 | Improves toughness, impact strength | 4340, 8640 | Often used in low-temperature applications |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.3–1.5 | Aids deoxidation, increases hardenability | 4140, 4150, 4340 | Very common, affects machinability |

| Tungsten (W) | 0.1–2 | Enhances high-temp strength, wear resistance | High-speed steels (M2, M42) | Less common in low-alloy steels |

| Vanadium (V) | 0.1–0.3 | Refines grain structure, increases hardness | Micro-alloyed steels | Often used in small quantities |

| Silicon (Si) | 0.2–2 | Improves strength, elasticity | Various alloy steels | Can affect oxidation resistance |

As you can see, the chemical composition determines how the steel behaves when subjected to cutting or drilling. Some alloy steel grades are more prone to work hardening, while others are known for their excellent toughness. In my own experience, properly matching the steel grade to your application is essential. If you pick a steel that’s too hard to machine, you’ll end up spending excessive time adjusting feeds and speeds. On the flip side, if you choose a less robust steel for a high-temperature environment, you risk premature failures.

Mechanical and Thermal Properties

Mechanical properties like tensile strength, yield strength, and hardness are crucial for understanding how a material will behave under load. Alloy steel typically possesses higher tensile strength compared to plain carbon steel, thanks to those alloying elements. That translates to better load-bearing capacity and wear resistance in applications like gears, shafts, and connecting rods.

Thermal properties also come into play when machining. Some alloy steel grades might have higher thermal conductivity, which helps dissipate heat more efficiently. Others might retain heat, increasing the risk of tool damage or changes in the steel’s microstructure.

I once ran a test with two different alloy steel bars, each about 2 inches in diameter. One was 4140, the other 4340. Using the same feed, speed, and coolant, I noticed that the 4340 part was slightly less prone to built-up edge formation. I suspect the nickel content improved toughness and distributed the heat differently.

Data and Graphical Analysis

Below is a second table that compares typical tensile strength, yield strength, and hardness ranges for some common alloy steel grades. These numbers can vary depending on heat treatment, but they offer a good starting point.

| Alloy Steel Grade | Tensile Strength (ksi) | Yield Strength (ksi) | Hardness (HRC) | Typical Applications | Heat Treatment Commonly Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4140 | 95–180 | 60–140 | 28–45 | Shafts, bolts, fasteners | Quenched & tempered |

| 4340 | 120–200 | 70–160 | 32–50 | Aircraft landing gear, crankshafts | Quenched & tempered |

| 5150 | 90–170 | 55–130 | 25–45 | Automotive parts (gears, axles) | Quenched & tempered |

| 8640 | 100–180 | 60–140 | 30–45 | Heavy machinery components | Quenched & tempered |

| 8620 | 90–120 | 50–80 | 20–30 | Gears, cams (case-hardened parts) | Carburizing + quench |

| 4145 | 110–200 | 70–150 | 30–50 | High-stress machinery components | Quenched & tempered |

| 4330 | 110–190 | 65–130 | 30–48 | Structural applications, drilling tools | Quenched & tempered |

This data underscores how each alloy steel responds differently, not just in terms of general toughness but also how it reacts to various heat treatments. Over the years, I’ve found it invaluable to keep these reference points on hand. They shape everything from my tool choice to my cutting strategies.

2.2 Machining Challenges and Solutions

Alloy steel can be both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, you get exceptional mechanical properties that let you build powerful machines, automotive components, and even high-performance weaponry. On the other hand, the same properties that make alloy steel so strong can complicate the machining process. I’ve personally snapped more than a few end mills in my time because I underestimated the complexity of an alloy steel workpiece.

Common Issues: Tool Wear, Work Hardening, and Heat Generation

Tool Wear:

One of the most common challenges I face when machining alloy steel is accelerated tool wear. The hardness of alloy steel can quickly dull cutting edges. Carbide tools are usually recommended, but even carbide inserts can chip if the cutting conditions aren’t optimized. I recall a situation where I was drilling a series of holes in a 4340 block. After about 10 holes, the drill bit showed significant flank wear. I adjusted the feed rate slightly and added more coolant. That got me a few more holes before I had to replace the bit.

Work Hardening:

Some alloy steel grades, especially those with higher chromium or nickel content, can exhibit work hardening. This means the material’s surface becomes harder as it’s being cut. If the feed rate or cutting speed is too low, you might just be rubbing the surface and driving up its hardness. Once the surface is work-hardened, future passes become even more difficult. That’s why I always recommend maintaining a sufficiently high feed rate to “cut through” the material rather than rubbing it.

Heat Generation:

Excessive heat is not just a tool-killer—it can also alter the microstructure of the alloy steel, leading to localized hardening or even warping. Coolant strategies are essential here. In a pinch, I’ve used high-pressure coolant systems to great effect, especially when performing high-speed machining. It helps flush chips away more effectively and keeps the part relatively cool. If your machine setup doesn’t allow for high-pressure coolant, using an air blast with a cutting fluid mist can be an alternative, though it’s not as robust.

Strategies for Optimizing Cutting Parameters

Optimizing cutting parameters is an ongoing balancing act. If you go too slow, you risk work hardening. Too fast, and you might burn up your cutting edges. Over the years, I’ve found the sweet spot by combining manufacturer recommendations with real-world experimentation.

Speed and Feed:

Generally, you want to reduce cutting speed compared to carbon steel but increase feed to ensure a healthy chip load. This combination helps you get under the hardened zone and move material efficiently. I typically start with something like 75% of the recommended speed for standard carbon steel, then adjust feed rates based on the chips I’m seeing.

Depth of Cut:

For roughing passes, you can go deeper if your machine has the horsepower and torque, but you want to maintain a consistent load on the tool. Sometimes, it’s better to take multiple moderate-depth passes rather than one extremely heavy pass, because alloy steel can stress your spindle and lead to chatter if you push it too hard.

Coolant Selection:

Using the right coolant can be the difference between a smooth run and a tool-wrecking fiasco. Full-synthetic coolants with high lubricity often work well for alloy steel. I like coolants that can handle high pressures. Plus, they need good anti-corrosion properties, because many alloy steel parts will sit for a while before the next operation.

Tool Selection and Cutting Fluid Technologies

The tool is where the rubber meets the road in machining. For alloy steel, I prefer coated carbides. Titanium nitride (TiN) coatings or titanium aluminum nitride (TiAlN) coatings can significantly improve wear resistance and reduce friction. Cobalt high-speed steel (HSS) tools can sometimes work for less demanding operations, but I’ve found that carbide is usually the go-to for serious production.

Cutting fluid technology also keeps evolving. Some shops are moving to near-dry machining, especially with environmentally friendly coolants or minimal quantity lubrication (MQL). But in my experience, alloy steel often calls for generous lubrication and cooling, so MQL might not be your best bet unless you’re dealing with a very specialized scenario.

2.3 Emerging Technologies and Trends

I’m always on the lookout for new ways to machine alloy steel more efficiently. Technology in this space moves quickly, from advanced CNC controllers to sensor-embedded tooling.

Digital Manufacturing and Smart Machining Solutions

We’re seeing an uptick in CNC machines that can dynamically adjust feeds and speeds based on real-time data. This goes beyond just a pre-programmed function. Some systems use machine learning algorithms to detect subtle changes in spindle load or vibration, then tweak the cutting parameters on the fly. It’s like having a seasoned machinist’s intuition built right into the machine. I’ve tested a system where the machine automatically reduced feed rate by 10% when it detected a spike in torque, preventing a potential tool crash.

Innovations in Monitoring and Process Control

I find it useful to install sensors on toolholders or even on the workpiece fixture. These sensors can measure temperature, vibration, and deflection. In alloy steel machining, these metrics are incredibly valuable. If temperatures spike, it might indicate insufficient coolant flow or excessive friction. If vibration levels become erratic, it could mean you’re flirting with chatter.

Future Developments in Alloy Steel Processing

While alloy steel is a well-established material category, metallurgists are continually refining compositions to achieve even better strength-to-weight ratios and improved machinability. We’re seeing steels that can be hardened more uniformly or that have microstructures optimized for lower friction. On the machining side, I believe additive manufacturing combined with subtractive post-processing will become a bigger deal. Imagine 3D printing a near-net shape in an alloy steel powder and then finishing it on a CNC mill. That’s already happening in some aerospace companies, though it’s not yet mainstream.

Practical Cases and Expert Insights

When I think about alloy steel machining in the real world, my mind goes back to several projects that taught me invaluable lessons. From the vantage point of experience, it’s one thing to read theoretical papers or watch videos on machining techniques. It’s a whole different ballgame when you’re on the shop floor, listening to the hum of CNC spindles and feeling the vibration through your fingertips as you carefully touch a freshly machined alloy steel part. In this section, I’m going to share a few in-depth practical cases, along with commentary from some of the most insightful experts I’ve had the privilege of meeting. My hope is that you’ll glean actionable tips and a better understanding of alloy steel machining nuances.

3.1 Automotive Industry: High-Performance Shafts

Let me start with one of the earliest large-scale projects I tackled: manufacturing high-performance transmission shafts for a racing team. The chosen material was a modified 4340 alloy steel, heat-treated to a hardness somewhere around 38–42 HRC. The reason 4340 was selected over simpler steels was its remarkable toughness, even at moderately high hardness levels. The material needed to withstand tremendous torque without snapping or deforming, especially under the dynamic stresses of a racing environment.

Machining Challenges:

- Tight Tolerances: We had tolerances as tight as ±0.0005 inches on critical diameters. This demanded not only a high level of CNC precision but also a robust process to minimize the risk of dimensional creep due to heat or tool deflection.

- Interrupted Cuts: Some sections of the shafts included splines and keyways, leading to interrupted cutting conditions. Each time the cutting tool re-entered the material, there was a risk of chatter or tool chipping.

- Production Volume: Because this was a racing team, we had to supply multiple sets of shafts for testing, spares, and final use. The volume might not sound huge (50 to 100 shafts per batch), but each shaft was expensive in terms of both material and machining time.

Solutions and Insights:

- Dynamic Balancing: We used milling machines and lathes equipped with real-time spindle load monitoring. The system would auto-adjust feed rate whenever it detected a load spike. This significantly reduced the risk of tool breakage during those tricky interrupted cuts.

- Optimized Coolant Strategy: We employed a high-pressure coolant system (about 1,000 psi) directed at the cutting zone. This was a game-changer for chip evacuation and temperature control. We noticed less thermal expansion on the parts and more consistent dimensional accuracy.

- Tooling Choices: For roughing, we used heavy-duty carbide inserts with a TiAlN coating. For finishing passes, a sharper, polished-edge insert yielded better surface finishes. By switching to specialized finishing inserts, we brought down our surface roughness from Ra 1.6 µm to Ra 0.8 µm.

One of the team’s lead engineers, Jason T., told me something that stuck: “When it comes to alloy steel, picking the right tool geometry can matter as much as the material itself. Don’t underestimate the effect of even small changes in corner radius or rake angle.” That advice helped me realize that every detail counts. Ultimately, we met the tight tolerances and delivered shafts that performed reliably under race conditions.

3.2 Aerospace Components: Landing Gear Mechanisms

Aerospace was another field where I saw alloy steel shine. I once consulted on a project that involved machining landing gear components from 300M steel, which is similar to 4340 but with additional silicon and vanadium to enhance strength. Landing gear faces enormous cyclic stress. The components must handle hard landings, temperature fluctuations, and the corrosive effects of deicing chemicals or saltwater (if operating near coastal regions).

Machining Challenges:

- Extreme Hardness: The 300M steel was heat-treated to around 50 HRC. This hardness level strained our tooling budget.

- Complex Geometries: The shapes involved deep pockets, undercuts, and internal thread holes that had to be meticulously machined without creating stress risers.

- Certification Requirements: Because this was for aerospace, traceability and repeatability were paramount. We needed to document every step, from how we measured raw material hardness to the coolant concentration used during milling, maybe it’s CNC Milling.

Solutions and Insights:

- High-Feed Milling: We opted for high-feed milling cutters for roughing out large volumes of material. This technique uses a small depth of cut but a high feed per tooth, allowing the tool to remove material more efficiently while minimizing cutting forces.

- Vibration Damping Toolholders: We introduced specialized toolholders with built-in dampers. At high hardness levels, chatter can become a significant issue. By employing these advanced toolholders, we reduced chatter and extended tool life by around 25%.

- Automation and Quality Control: We integrated a robotic arm to move parts between operations. Each part was measured using an in-process probing system to ensure dimensional consistency. The data was automatically logged for certification audits.

I discussed these processes with a fellow consultant, Paula M., who specializes in aerospace CNC programming. She mentioned that, in her experience, “the compliance and documentation overhead in aerospace can be as big a challenge as the actual machining.” From her standpoint, combining robust machining strategies with real-time data logging was a must. Having seen it firsthand, I fully agree.

3.3 Heavy Machinery: Large Forged Components

Switching gears to heavy machinery, I was once involved in producing large forged shafts and gears for industrial presses. We’re talking about alloy steel components that weighed hundreds of pounds. In such scenarios, material handling alone can be a challenge. It’s not easy to maneuver these massive blanks on and off lathes or mills, particularly when you need tight alignment.

Machining Challenges:

- Massive Heat Generation: The sheer size of the parts meant a lot of energy went into cutting. Heat buildup could be substantial, risking dimensional distortion in the part and premature tool failure.

- Machine Rigidity: We needed extremely rigid equipment to handle the forces involved. On one project, the torque required to cut a 12-inch diameter forging was intense enough that a less robust machine could have deflected or stalled.

- Logistics and Setup Times: Every part shift from one machine to another took significant crane time, increasing the total production lead time.

Solutions and Insights:

- Segmented Machining Strategies: We broke down the operation into smaller zones. Instead of trying to machine an entire surface in one continuous pass, we scheduled multiple passes that focused on specific segments. This let the part cool between passes, minimizing thermal distortion.

- Specialized Fixturing: We designed custom fixtures that bolted securely onto the forging. This provided a stable datum, so each re-chucking was consistent. Even a small misalignment on these large parts can translate into big dimensional errors.

- Coolant Flooding System: We used a flooding approach with a water-soluble coolant. The setup delivered coolant from multiple nozzles at different angles, ensuring coverage of both the tool and the emerging chip stream.

While working on these parts, I had a chance to speak with a veteran machinist, Robert D., who’d been in the trade for over 40 years. Robert told me, “With heavy forgings in alloy steel, patience is key. It’s easy to push too hard and cause catastrophic tool damage. A balanced approach always wins.” I found that bit of wisdom priceless.

3.4 Oil & Gas Industry: Pipe Couplings and Valves

The oil and gas industry often deals with alloy steel that must resist corrosive downhole conditions, extreme pressure, and abrasive drilling fluids. For instance, 4145 and 4330 variants appear in tool joints, pipe couplings, and valve bodies. I once took part in a project where we had to produce custom valve assemblies rated for high-pressure service in offshore drilling.

Machining Challenges:

- Corrosion-Resistant Coatings: Some parts needed additional coatings, like tungsten carbide overlays, making certain areas even more challenging to machine.

- Threading Operations: Internal and external threads often had to meet API (American Petroleum Institute) specs, which come with their own set of precise tolerances and acceptance criteria.

- Field Repairs: In many cases, these components needed to be repaired or re-machined in the field. That meant developing processes that operators could replicate in less-than-ideal conditions, sometimes on a rig far from a well-equipped shop.

Solutions and Insights:

- Thread Milling vs. Tapping: In certain cases, we switched to thread milling to ensure tighter dimensional control and reduce the risk of tap breakage in these hard alloy steel parts.

- Portable Machining Units: We experimented with portable lathes and milling attachments that could be clamped onto pipe sections in the field. This is a niche solution but vital for remote repairs.

- Corrosion-Resistant Materials: Sometimes the best machining approach is to select a more machinable variety of alloy steel that still meets performance specs. We found that reducing chromium slightly in the steel’s composition improved machinability without significantly harming corrosion resistance, at least for certain operating conditions.

During a site visit to a Gulf Coast repair facility, I watched a team quickly re-machine a valve seat using a portable boring bar system. Despite having less horsepower and rigidity than a conventional CNC mill, they managed to achieve the required surface finish. It was a testament to both skill and the adaptability required for the oil and gas world.

3.5 Expert Roundtable: Key Perspectives on Alloy Steel Machining

Beyond these industry-specific cases, I’ve had the opportunity to attend workshops and informal gatherings where seasoned professionals discussed alloy steel machining challenges. Here are a few distilled insights that I found particularly helpful:

- Tool Coatings Matter: Many experts emphasize that modern tool coatings can vastly improve your throughput. PVD coatings like AlTiN or TiAlN can reduce friction and extend tool life.

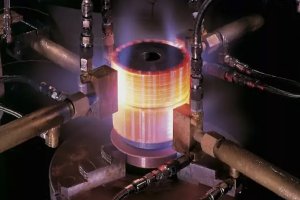

- Heat Treatment Integration: If you have the flexibility to control heat treatment in-house, you can experiment with slightly softer steels for rough machining and then perform a final heat treatment and a finishing pass. This approach can save you tons of time and money on tooling.

- Custom Coolant Blends: Some shops collaborate with coolant suppliers to develop custom blends specifically for their alloy steel processes. These blends can include additives that enhance lubricity or inhibit corrosion.

- Data Logging and Analysis: The best-run operations gather as much data as possible—cutting forces, spindle loads, tool life, and more. By analyzing trends, they fine-tune their processes to squeeze out every ounce of efficiency.

One of my favorite experts to consult is Greg L., who runs a large precision machine shop. Greg has this quip: “If you’re not collecting data, you’re guessing. And guessing with alloy steel can cost you big.” I’ve seen the truth in that statement when I tried to rely on gut feeling alone. Over time, adopting a data-driven mindset has made a measurable difference in my results.

3.6 Personal Reflections on Challenges and Rewards

I’d be lying if I said every project I’ve worked on with alloy steel was an immediate success. I’ve had my share of scrapped parts, broken tools, and late-night epiphanies that forced me to rewrite entire machining programs. Yet, there’s something uniquely satisfying about getting it right. The payoff for mastering alloy steel is huge:

- You can tackle higher-value projects that require materials with advanced mechanical properties.

- You build a reputation as a shop or machinist who can handle the toughest jobs.

- You learn skills that transfer to other high-performance alloys, from stainless steel to superalloys.

It’s also personally rewarding. Whenever I see a complex alloy steel component that I helped produce, whether it’s on a racetrack, an airplane, or a drilling rig, it’s a reminder of what’s possible when we combine craftsmanship with engineering know-how.

Comprehensive Guidelines and Resource Recommendations

There’s a moment in every machining project when I realize I need a concise, go-to set of guidelines—something to confirm that I’m on the right track and that I’m not missing important details. Over time, I’ve accumulated a personal toolbox of best practices, parameter recommendations, troubleshooting steps, and resources specifically for alloy steel. I’ll lay them all out here. My goal is to provide you with what I wish I’d had years ago: a solid, one-stop reference for alloy steel machining.

4.1 General Machining Best Practices

4.1.1 Material Selection and Pre-Processing

- Grade Choice: Always pick the alloy steel grade that matches your application’s load, temperature, and corrosion requirements. If I’m dealing with mid-level stresses, something like 4140 or 4340 works great. For extreme stress, I might consider 300M or other ultra-high-strength steels.

- Heat Treatment Strategy: I’ve learned that controlling the heat treatment process can save a lot of hassle. If the steel is too hard, roughing operations become a nightmare. If possible, do your roughing passes in an annealed or normalized state, then heat-treat, and finally perform finishing passes.

- Pre-Machining Inspection: Before starting, I typically check for surface defects, decarburization layers, or scaling. Removing these early on can prevent tool damage and dimensional surprises. Sometimes, forging scale can be extremely abrasive, especially on certain alloy steel variants.

4.1.2 Tooling Essentials

- Tool Material: In most cases, carbide is the way to go. High-speed steel can handle simpler tasks or soft states, but carbide inserts, especially with PVD or CVD coatings, almost always yield better tool life on tough alloy steel.

- Geometry Considerations: A slightly negative rake can help in heavy-duty applications, but for finishing, I often switch to positive or neutral rake inserts. I avoid overly large corner radii unless the part geometry calls for it, because larger radii can raise cutting forces.

- Toolholding and Spindle Integrity: The more robust your setup, the better. If you can, invest in high-quality toolholders with minimal runout. Any vibration or chatter can quickly ruin the surface finish and accelerate tool wear.

4.1.3 Cutting Parameters

- Speeds and Feeds: I generally run about 20–30% slower in surface feet per minute (SFM) than I would for a mild steel, but I increase feed slightly to avoid rubbing. Starting with conservative speeds—say 200 SFM for typical alloy steels—and then adjusting upwards works for me.

- Depth of Cut: For roughing, a moderate depth of cut (0.1–0.2 inches) can be effective if your machine can handle the load. For finishing, I go lighter (0.01–0.05 inches) to reduce deflection.

- Coolant Flow: High-pressure coolant is a big plus, but even if you don’t have that option, ensure you have ample coolant flow directed at the cutting zone. I also like using through-tool coolant for drilling operations.

4.1.4 Chip Control

- Chip evacuation is critical. When chips aren’t cleared, they can get re-cut, generating more heat and dulling the tool. For turning operations on tough alloy steel, I use chipbreakers designed for heavier materials.

- Chip color can provide clues about your cutting parameters. Straw-colored or light blue chips often mean you’re near the sweet spot. Deep blue or purple chips might mean excessive heat.

4.2 Specific Operations: Turning, Milling, Drilling, and More

Given the variety of operations involved in machining alloy steel, I want to offer guidelines tailored to each. Over the years, I’ve found that small tweaks in each operation can add up to a massive improvement in throughput and part quality.

4.2.1 Turning

- Insert Selection: For rough turning on alloy steel, a robust CNMG or DNMG insert with a medium chipbreaker is popular. Finish turning might employ a less aggressive chipbreaker with sharper edges.

- DOC (Depth of Cut) vs. Feed: Balancing these factors is crucial. A deeper DOC with a moderate feed can be more stable than a shallow DOC with an extremely high feed.

- Constant Surface Speed: Many CNC lathes offer constant surface speed (CSS). Utilizing CSS helps keep your cutting speed consistent, leading to more predictable tool wear and better finishes on alloy steel.

4.2.2 Milling

- High-Feed Milling: I’m a big fan of high-feed milling for roughing out large amounts of alloy steel. The approach uses shallow depths of cut but very high feed per tooth, effectively directing cutting forces axially and extending tool life.

- Climb vs. Conventional Milling: Generally, climb milling is recommended on rigid machines for better surface finishes and longer tool life. Conventional milling can be useful for removing scale or hardened layers, but it can also accelerate insert wear.

- Tool Path Strategies: Adaptive milling strategies in modern CAM software let you maintain a consistent chip load. This is extremely beneficial for tough materials like alloy steel, as it prevents sudden load spikes on the cutter.

4.2.3 Drilling and Hole-Making

- Split-Point or Self-Centering Drills: If you’re still using standard twist drills on alloy steel, you’re missing out. Carbide drills with self-centering geometries significantly improve hole position accuracy and chip evacuation.

- Peck Drilling: For deep holes, peck drilling helps remove chips that can pack into the flutes. However, too many pecks can increase cycle time and risk work hardening the hole walls. I often use a minimal peck approach or specialized “chip break” cycles.

- Pilot Holes and Boring: For critical holes, I sometimes pilot-drill first, then move to boring operations. Boring delivers excellent diameter control and surface finish but can be slower.

4.2.4 Tapping and Thread Milling

- Rigid Tapping: Some CNC machines offer rigid tapping, which synchronizes the spindle and feed precisely. This reduces the risk of stripping threads or breaking taps in hard alloy steel.

- Thread Milling: I’ve become a champion of thread milling in many alloy steel applications. It’s more forgiving if the tool breaks, and you can adjust the thread fit by tweaking the tool path.

4.3 Troubleshooting Common Machining Issues

No matter how carefully I plan, hiccups happen. Below are some frequent issues and quick troubleshooting tips that might save you from scrapping expensive alloy steel parts.

| Issue | Potential Causes | Quick Fixes |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive Tool Wear | – Too high cutting speed – Inadequate coolant flow | – Reduce cutting speed – Upgrade coolant or increase flow |

| Poor Surface Finish | – Chatter or vibration – Dull insert | – Check rigidity, try a different insert geometry – Use a finishing insert |

| Built-Up Edge (BUE) | – Insufficient feed – Excessive heat | – Increase feed slightly – Improve coolant or switch to better coating |

| Work Hardening | – Low feed rate – Rubbing instead of cutting | – Increase feed to ensure a real cut – Use sharp tools or robust inserts |

| Dimensional Inaccuracy | – Thermal expansion – Inconsistent tool deflection | – Schedule cooldown breaks – Use in-process measurements / probing |

| Chip Jamming | – Poor chip evacuation – Inadequate chipbreaker design | – Adjust feed and chipbreaker – Use higher coolant pressure |

| Drill Walk-Off | – Improper drill point – Misalignment in fixturing | – Use self-centering carbide drills – Re-check fixture alignment |

Practical Tips from My Own Experience

- Listen to the Cut: Sometimes I can hear when something is off. If the cut sounds “squealy” or labored, I suspect insufficient feed, poor tool geometry, or a lack of rigidity.

- Regular Tool Checks: Even with brand-new inserts, I frequently inspect them after the first few parts. Alloy steel can wear edges faster than I expect, especially on long production runs.

- Document Everything: Keeping a log of speeds, feeds, insert types, and notes on how the machining run went can make your next alloy steel job far smoother.

4.4 Resource Recommendations

I strongly believe that the learning never ends, especially in machining. The field evolves so quickly that staying current can be a challenge. Below are my favorite resources for continuous improvement in alloy steel machining.

- Machinery’s Handbook: This classic reference includes a wealth of data on steel properties, recommended feeds and speeds, and other manufacturing processes.

- CNC Manufacturer Guides: Leading CNC machine manufacturers (like Haas, Mazak, DMG Mori, etc.) often release PDF guides or tutorials on best machining practices. Check their websites or talk to your local rep.

- Tooling Supplier Data: Companies like Sandvik, Kennametal, and Iscar provide detailed charts and calculators for alloy steel. I frequently consult their catalogs for recommended cutting parameters and geometry tips.

- Online Machinist Forums: Websites like Practical Machinist or CNCZone have active communities. Searching for “alloy steel” yields a plethora of real-world advice. You can post questions and usually get a response from someone who’s faced the same problem.

- Industry Conferences & Trade Shows: Events like IMTS (International Manufacturing Technology Show) or EMO provide a snapshot of the newest tooling, machine tools, and software solutions. It’s a fantastic way to pick up tips on alloy steel machining from company reps and industry pros.

- Vendor Training & Seminars: Sometimes, the best knowledge transfer happens in person. I’ve attended seminars hosted by tooling companies that focus entirely on machining tough materials like alloy steel and Inconel. They often bring sample parts, run live demos, and answer your specific questions on the spot.

4.5 Building a Continuous Improvement Culture

In my own shop, we try to foster an atmosphere of constant learning. That means:

- Regular Team Meetings: We discuss wins and losses. If someone found a sweet spot for cutting speed on 4340, they share it so everyone benefits.

- Cross-Training: Machinists learn not just turning but also milling, drilling, and even programming. That holistic view helps them see the bigger picture when working with challenging alloy steel applications.

- Data Analysis: We compile metrics on tool life, part cycle times, scrap rates, and rework percentages. We then look for trends. Maybe we discover that certain types of coolant are leading to consistently better finishes. Or we see that our first-shift team is more efficient than second shift. Why? Data can point us to the answers.

I’ve witnessed shops that treat every job as a chore, simply repeating the same routines. By contrast, shops that embrace these guidelines—monitoring, refining, and evolving their approach—tend to stand out. Not only do they attract bigger contracts, but they also offer a more satisfying work environment. People get excited about problem-solving and innovation. When you’re dealing with alloy steel, that passion can translate directly into better parts, fewer scrapped materials, and a healthier bottom line.

4.6 Personal Commentary on Moving Forward

I sometimes look back on the day I first attempted to machine a hardened piece of 4340 and feel a bit nostalgic. It was a frustrating experience, but it’s those early lessons that pushed me to compile these guidelines. If you’re new to alloy steel or if you’ve struggled in the past, I hope this section helps you sidestep a few pitfalls.

My biggest advice is to remain flexible. Alloy steel is not a monolith; it has many forms and each one can behave differently, especially under varied heat treatments or end-use conditions. The key is to build a knowledge base and gather resources—like the ones listed here—so you can adapt and fine-tune your process. Over time, you’ll develop a sixth sense for how to approach each new job. And if you continue to innovate and learn, I promise the results will be worth it.

Conclusion and Outlook

I remember the first time I ever encountered alloy steel. It was a small test piece—a leftover from someone else’s project—and I had no idea how different it would feel under the mill compared to plain carbon steel. Right away, I noticed the tool vibration and the distinct coloration of the chips, and I realized that I was dealing with something entirely different. Over the years, I’ve come to appreciate just how versatile, challenging, and rewarding alloy steel can be.

One major takeaway is that alloy steel isn’t static. Metallurgists are always refining compositions, adding small percentages of elements like vanadium, chromium, tungsten, or nickel. Each addition has a ripple effect on properties like toughness, hardness, and even machinability. That’s why we see new grades emerging, aiming to strike a balance between performance and ease of processing. For instance, some of the newer micro-alloyed steels are easier to machine than their predecessors, which can lower tooling costs and increase throughput for manufacturers.

Going forward, I see the machining of alloy steel becoming increasingly data-driven. We already have CNC machines that rely on sensors and real-time monitoring to adjust toolpaths or feed rates on the fly. In the near future, I envision even more sophisticated systems that can identify micro-level changes in the steel’s structure. We might see in-process scanning technologies that analyze the surface hardness or detect minute microcracks before they become a real issue. That’s the direction modern manufacturing is headed: tighter control, smarter automation, and predictive analytics.

Another area that will likely see growth is additive manufacturing of alloy steel. Right now, most 3D printing with metals focuses on materials like stainless steel, titanium, or specialized superalloys used in aerospace. However, as the cost of metal powders comes down and printing methods improve, I expect to see more shops experimenting with alloy steel powders. The biggest challenge is ensuring that the printed material retains the mechanical properties we rely on. We might need post-print heat treatments, hot isostatic pressing, or other densification techniques to achieve the strength and toughness we expect from conventional forging or rolling processes.

I also think about the environmental impact. Traditional machining of alloy steel can be resource-intensive, especially when we consider coolant usage, energy consumption, and the disposal of metal shavings. As sustainability becomes a greater concern, I believe more shops will switch to minimal quantity lubrication (MQL) or advanced coolant filtration systems. We’ll likely see new cutting fluid chemistries that are biodegradable and still provide the lubricity and thermal control required for tough materials like alloy steel.

In addition, the knowledge pool surrounding alloy steel continues to expand. Universities, research institutes, and even large manufacturing enterprises regularly publish papers on improving machinability. This collective effort drives innovation in tool coatings, geometry, machine design, and process optimization. Whenever I attend a manufacturing conference, there’s always a talk or demonstration devoted to tackling the challenges of hardened or exotic steels. It’s inspiring to watch new engineers and machinists approach alloy steel with fresh perspectives.

Looking at the bigger picture, alloy steel isn’t going anywhere. Its unique combination of strength, ductility, and fatigue resistance makes it indispensable in industries as varied as automotive, aerospace, oil and gas, nuclear power, and infrastructure construction. The journey from forging to finished part will keep evolving, but alloy steel will remain a cornerstone of critical applications. As more manufacturing processes go digital, we’ll see faster feedback loops—machinists can quickly spot issues and respond with adjusted speeds, feeds, or tooling.

I also believe training and education will have to keep pace. Not every machinist or engineer starts off understanding the finer points of alloy steel. That’s why I’ve been an advocate for structured apprenticeship programs and continuing education courses. If you give people the right foundation—if you teach them how to analyze microstructures, interpret hardness charts, or choose the right heat treatment—they’ll be empowered to explore new techniques. They won’t be intimidated by tough materials; they’ll be motivated to tame them.

Personally, I hope that what I’ve shared in these chapters serves as a bridge between academic theory and shop-floor reality. So many times, I’ve seen people struggle with alloy steel simply because they underestimated it. But with knowledge comes confidence. When you can walk up to a CNC machine, load a piece of 4340 or 300M steel, and say, “I know exactly how I’m going to approach this cut,” you feel empowered. You’re not only saving time and money; you’re embracing the challenge head-on.

Meanwhile, I can’t help but marvel at how far we’ve come. Decades ago, we didn’t have high-speed steel or carbide tooling at the level of sophistication we do now. We didn’t have advanced CAD/CAM systems that could model our entire toolpath. And we certainly didn’t have real-time sensor feedback that let us see, second by second, how our alloy steel workpiece was holding up. Yet here we are today, forging ahead with an ever-evolving technology suite, turning what used to be a rough guesswork process into a precise, data-backed science.

If I had to guess what might change the alloy steel landscape the most in the next decade, I’d point to ongoing research in nanostructured steels or steels that incorporate graphene. We could see leaps in wear resistance without sacrificing machinability. At that point, we’d have to adapt all over again, learning new cutting parameters, new heat treatment protocols, and new ways of verifying part quality. I, for one, can’t wait to see it happen.

But for now, what matters is that we continue refining our approach to the alloy steel grades we already know. Whether you’re dealing with 4140, 4340, 8640, or some custom blend, the key is to keep learning and iterating. Monitor your process, capture data, talk to your tooling suppliers, and never stop experimenting. That’s what will keep us pushing the boundaries of what’s possible.

To wrap up: alloy steel machining is both an art and a science. It calls for a methodical approach—selecting the right tool materials, adjusting speeds and feeds, managing heat, and understanding the microstructure—yet it also rewards creativity and intuition. As I look to the future, I see more collaboration between researchers, machinists, and manufacturers, all working together to get the most out of these remarkable steels. By sharing our experiences and insights, we elevate the entire industry. And that, to me, is the real promise of alloy steel: a collaborative journey where each success story inspires the next.

FAQ

Below you’ll find an expanded FAQ section with 18 common questions related to alloy steel machining. I’ve written them from my own perspective, blending personal experience with industry knowledge. Each answer is designed to be comprehensive, and in some cases, I’ve woven in anecdotes that illustrate critical points.

6.1 What is alloy steel, and how does it differ from carbon steel?

Alloy steel is a category of steel that includes additional alloying elements such as chromium, nickel, molybdenum, or vanadium in specified amounts. These elements enhance properties like strength, toughness, corrosion resistance, and hardness. In contrast, carbon steel primarily relies on carbon content for its mechanical properties. From my experience, alloy steel often offers better performance in high-stress or high-temperature environments, but it can also be more challenging to machine.

6.2 Why is alloy steel commonly used in high-stress applications?

In my earlier days as a machinist, I worked on an automotive racing project that used alloy steel for engine components. The reason was simple: alloy steel can maintain its strength under stress and temperature extremes. By adding elements like molybdenum or chromium, the steel can handle loads that would cause lesser materials to fail. This makes it ideal for parts like gears, shafts, and fasteners that endure repetitive or heavy-duty impacts.

6.3 What are the key properties of alloy steel that impact machinability?

Properties such as hardness, toughness, and thermal conductivity play major roles in machinability. For instance, a very tough alloy steel might resist cutting, causing tool wear to spike. Meanwhile, steels with lower thermal conductivity can cause excessive heat buildup. When I first machined a nickel-rich alloy steel, I realized the chips weren’t carrying the heat away like they did with standard carbon steel, so I had to adjust my cutting speeds and use more aggressive coolant strategies.

6.4 How does the chemical composition of alloy steel affect its machinability?

Each alloying element influences machinability in different ways. Chromium enhances corrosion resistance but can also make the steel more abrasive on cutting tools. Nickel improves toughness, helping the part stand up to impacts, yet it can increase work hardening. Molybdenum bolsters high-temperature strength. Balancing these elements is an art form in metallurgy. In a project I tackled involving 4340, I had to account for both the chromium and nickel content by reducing my cutting speed and using a high-pressure coolant system to manage tool wear.

6.5 What are the main challenges encountered during machining of alloy steel?

Tool wear, heat generation, and work hardening are the three big ones in my book. The moment you start cutting a harder grade of alloy steel, you notice how quickly tool edges can break down. Generating excessive heat can also distort the part’s microstructure or cause dimensional inaccuracies. Work hardening, especially in steels with higher nickel or chromium content, can make subsequent passes even tougher if your feed is too low or if you dwell too long in one spot.

6.6 Which machining processes are most suitable for alloy steel?

Turning, milling, and drilling remain the cornerstones. However, in my experience, certain advanced operations like high-feed milling or trochoidal milling can offer real advantages. High-feed milling uses shallow cuts but large feed rates, which can help with chip evacuation and reduce the risk of chatter. Trochoidal milling, often enabled by modern CAM software, maintains a consistent tool engagement angle, improving tool life and surface finish when dealing with tough alloy steel.

6.7 How can tool wear be minimized when machining alloy steel?

I focus on three main aspects: choosing the right tooling material (usually carbide with specialized coatings), optimizing cutting parameters (slower speeds, higher feeds), and managing heat with good coolant flow. If I see signs of flank wear or chipping, I might adjust the speed by 5–10% or switch to a more wear-resistant coating like AlTiN. Regularly inspecting the tool and recording wear patterns also helps you predict when the tool will reach its limit.

6.8 What role do cutting fluids play in the machining of alloy steel?

From my perspective, cutting fluids (coolants) are indispensable for alloy steel. They perform multiple roles: cooling, lubricating, and flushing away chips. When I’ve tried cutting tough steels without adequate coolant, tool life plummeted, and finishes got rough. Sometimes, a specialized or synthetic coolant works better, especially one designed for extreme-pressure conditions. If your machine has a through-spindle coolant system, even better—it helps keep the cutting zone stable and chips under control.

6.9 How does heat generation during machining affect alloy steel?

Heat can cause localized hardening, micro-cracks, or dimensional warping in alloy steel. I once ran into a scenario where a part’s tolerance was shifting by a few thousandths between passes. It turned out the part was retaining heat, expanding slightly, then cooling later to a different dimension. Controlling heat generation with proper speeds, feeds, coolant, and even scheduling breaks in the process can help mitigate these issues.

6.10 What are the best practices for selecting cutting tools for alloy steel?

Start with carbide inserts or solid carbide tools, often with a PVD or CVD coating like TiN, TiAlN, or AlCrN. Look for geometries that are designed for heavy-duty or tough materials. Tool holders with high rigidity also make a difference. I’ve personally had success with negative-rake inserts for roughing on extremely hard steels, then switching to a positive-rake insert for finishing to get a better surface finish. Always consult tooling manufacturer catalogs; they usually provide recommended parameters specifically for alloy steel.

6.11 How can machining parameters be optimized for better surface quality?

Surface quality often depends on stable cutting conditions—so minimize vibration, ensure adequate coolant, and select the right feed and speed combination. Sometimes I’ll see machinists try to dial up the speed too high, hoping for a smooth finish, but with alloy steel, you can end up scorching the surface. I usually maintain a moderate speed and ensure a consistent chip load. For truly fine finishes, a wiper insert can help smooth out the peaks and valleys on the workpiece.

6.12 Are there specific digital technologies that aid in alloy steel machining?

Absolutely. We now have CNC controllers that continuously monitor spindle load, torque, and even acoustic signals. If they detect a sudden increase in cutting forces—maybe from a built-up edge or unexpected hardness variation—they can automatically adjust feed rates. I’ve worked with systems that tie into cloud-based dashboards, letting shop managers see tool performance across multiple machines in real time. This big-data approach helps identify trends, like which brand of inserts lasts longest on 4140 or how different batch heat treatments affect tool life.

6.13 What are some recent innovations in alloy steel processing?

One area is near-net-shape forging, where the forging process creates parts very close to final geometry. This reduces the total amount of machining needed. Another is vacuum carburizing, which can enhance surface hardness while maintaining core toughness. For me, the combination of advanced heat treatments and improved forging techniques means fewer hours on the machine, lower tool wear, and better consistency in alloy steel properties across each batch.

6.14 How do experts approach troubleshooting machining issues with alloy steel?

Experts typically follow a systematic approach:

- Identify the Symptom: Excessive flank wear, chatter, poor surface finish, or dimensional drift.

- Check the Basics: Tool condition, fixture rigidity, coolant flow, and correct feed/speed settings.

- Gather Data: Tool-life charts, vibration readings, temperature measurements.

- Implement Incremental Changes: Adjust one parameter at a time, observing the effect.

- Document the Outcome: Successful adjustments become part of a standard operating procedure.

I’ve personally found that focusing on data makes the biggest difference. If you simply guess, you might fix the symptom once, but you won’t have a blueprint for future jobs.

6.15 What resources and guidelines are available for further learning on alloy steel machining?

Many resources are out there:

- Machinery’s Handbook is a staple.

- Tool Manufacturer Websites like Sandvik, Kennametal, or Iscar provide cutting data.

- Online Communities such as Practical Machinist or CNCZone have lively discussions on alloy steel.

- Workshops and Trade Shows like IMTS or EMO.

I often share experiences in these spaces and pick up new tips from peers who’ve tackled similar problems.

6.16 How does heat treatment interplay with machining strategy for alloy steel?

Heat treatment can make or break your machining plans. If a part is quenched and tempered to a very high hardness, you’ll need more robust tooling and slower cutting speeds. Some manufacturers rough-machine their parts in an annealed condition, then perform heat treatment, followed by a final finishing pass. I’ve seen shops reduce total machining hours by half using this approach, especially for complex alloy steel components.

6.17 Can alloy steel be machined using near-dry or dry machining methods?

It can be done, but it’s not always straightforward. Near-dry machining or MQL (Minimum Quantity Lubrication) relies on minimal coolant usage. This can work if your alloy steel part is somewhat softer, or if you’re not removing a huge volume of material. I’ve tried MQL on a well-annealed 4140 and got passable results, but I wouldn’t dare use it on a hardened 4340. The main issue is heat buildup. You need to ensure that the reduced coolant won’t cause excessive tool wear or thermal distortion.

6.18 What’s the single most important takeaway for success with alloy steel machining?

In my view, it’s to remain flexible and data-driven. Alloy steel covers a wide range of compositions and hardness levels. What works for 4140 at 32 HRC might fail for 4340 at 48 HRC. By systematically experimenting with speeds, feeds, and tooling setups—and carefully recording your results—you build a knowledge bank that can guide future projects. Don’t be afraid to adapt. Once you do, you’ll find that alloy steel goes from being an intimidating adversary to a fascinating challenge you can master.

Other Articles You Might Enjoy

- C-276 Alloy CNC Machining: Challenges, Solutions, and Best Practices

Introduction to C-276 Alloy 1.1 Why C-276 Alloy? When I first encountered c-276 alloy, I was looking for a material that could withstand harsh chemicals in a high-temperature environment. My team…

- Mastering Titanium Alloy Machining: Challenges, Techniques, and Industry Applications

Chapter 1: Introduction When I first began working with Titanium Alloy, I was struck by how unique they were. These materials combine high strength, low weight, and exceptional resistance to…

- Zinc Alloy Machining Demystified: From Properties to Advanced Techniques

Introduction Zinc alloy is a fascinating material that I’ve encountered many times in my work with various manufacturing teams. I remember the first project where we used zinc alloy for…

- Understanding AISI 4140: The Ultimate Guide for CNC Machinists

Introduction to AISI 4140: A Versatile Alloy Steel When it comes to CNC machining, material selection is crucial, and AISI 4140 stands out as one of the most versatile and…

- Tackling Tough High-Temperature Alloys in CNC Machining with Sand Blasting Glass Beads

High-temperature alloys, also known as superalloys, are designed to withstand extreme environments where ordinary materials would fail. These alloys are crucial in industries such as aerospace, power generation, and chemical…

- 316 Stainless Steel Machining: Best Tools, Cutting Speeds, and Techniques

Introduction I’ve worked with all kinds of metals in various shops. Over time, I’ve come to see why 316 stainless steel is so widely used. It’s sturdy, corrosion-resistant, and can handle many…

- 304 Stainless Steel: Properties, Applications, Machining, and Buying Guide

Introduction I still recall the day I had to choose a material for a small test project back when I was just starting out in fabrication. My mentor insisted on…

- Machining Techniques for Parts: Unlocking CNC and Cutting-Edge Tech

I. Introduction I remember the first time I realized how critical machining is to modern manufacturing. I was interning at a small shop, watching a CNC machine carve intricate features…